Dr. Gunni—Iceland’s eminent scholar of rock and pop music—is finally coming out with the long-promised English language version of his super educational, super detailed treatise on the history of Icelandic popular music. The book leaves no stone unturned and is a must-read for any serious fan of Icelandic music, providing context and history to all those hot young rock bands you guys like so much, adding understanding and appreciation.

‘Blue Eyed Pop – The History of Popular Music in Iceland’ is set to hit bookstores at the end of the month, but in the meantime the good doctor has graciously offered us the chance to print a chapter from the book. Read on to learn about how rock ‘n’ roll first hit Iceland’s shores and fascinated the nation… then read a bit further for our conversation with Gunni, which was as educational as you would expect.

The history of popular music pre-rock ‘n’ roll is of course rich and ripe with development and grand ideas. However, rock music just seemed so revolutionary when it appeared on the scene that everything that came before it was weighed against it, and was almost outdated on the spot. Rock ‘n’ roll was the spanking, shiny new plaything. Rock music defined a group of consumers, teenagers, who sprang out fully formed as a particular target market, a hitherto unknown demographic that was ripe for the tapping. Rock music also brought forth a severe generation gap, as it mostly appealed to the younger generation. Before rock, most age groups were on the same boat when it came to popular music—mom, grandma and the kids would listen to the same artists and dance the same dances.

Powerful and primitive

In Iceland, news of this exciting new form of music spread fast. In December of 1955, one Dean Bowling, an American soldier on leave from the Keflavík base, became the very first person to sing rock music in Iceland. He appeared with Carl Billich’s band at an Íslenskir tónar revue and sang “Rock Around the Clock,” “Shake, Rattle and Roll” and a few more early rock songs. People liked what they heard, but this appearance had a limited impact.

When rock music was first played on the state radio station, it was to a much greater effect. It was beloved singer Haukur Morthens who first blasted rock ‘n’ roll over the Icelandic airwaves at his weekly radio show, early in 1956. A foresighted stewardess had brought him Elvis Presley’s “Heartbreak Hotel” single, suggesting he play it in his show. Haukur obliged. “It sounded so unworldly and crass. So much beat, so much jabber. Today it sounds just easy and cosy,” Haukur would comment thirteen years later, in an interview with the magazine Vikan. The kids loved what they heard, but legend has it that in Höfn í Hornarfirði, a farmer suffered a heart attack spurred by Elvis sounding through his radio.

Soon larger doses of rock ‘n’ roll were played on the radio, much to the dismay of many. “This filthy American noise will spoil the youth,” the cultural elite would say, adding: “Thankfully, rock music is just a bubble that will burst soon enough.” Besides getting their dose of rock from Icelandic state radio, kids living in the southwest corner of Iceland could tune in to the US naval base radio and hear brand new rock tunes amid songs from respectable performers such as Frank Sinatra, Bing Crosby and the Andrews Sisters.

As was customary, it was down to merchant sailors to bring in the good stuff. “A sailor who lived in downtown Keflavík would blast rock ‘n’ roll out of his window,” said Rúnar Júlíusson, future member of the main beat band, Hljómar. “This is where I first heard rock music; Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis and especially Chuck Berry really fired me up. This sounded so powerful, yet so primitive. This was not like anything I had heard before.”

Early American rock ‘n’ roll films were shown in Reykjavík’s theatres as early as 1957. ‘Rock Around the Clock,’ featuring Bill Haley and The Platters among others, was the most influential of those, almost causing a riot in the cinema when it was shown—as it had done in various other European cities.

But watching a film was nothing compared to the real thing. The first rock ‘n’ roll combo in Reykjavík was performed in 1957 by Tony Crombie and his Rockets. Tony was a British drummer and a former jazzist who had jumped on the rock bandwagon. His band staged a convincing rock show night after night at the Austurbæjarbíó cinema, having performed in front of estimated total of ten thousand Icelanders when their stint ended. Sometimes the police were brought in to calm down rock crazy teens that danced in the aisles and even outside the cinema after the show was over.

The kids go for it

Icelandic musicians at the time, most of them jazz fans, didn’t like this new fad at all. Some of them had gone to see Tony Crombie and his crew play. They didn’t like the music, but were thrilled by the amount of gear on stage and thrown back by the sheer volume of the music. “This is crap music, if you can call it music at all,” the jazzists would say, yet they were forced to play “the crap” because the kids and the young audience liked it so much. Rock ‘n’ roll was all they asked for at the dancehalls. Elaboration and professionalism were the values musicians worked by, and they had a hard time grasping manic, cathartic venting that came along with rock music.

Those who fell for the fresh and powerful music were kids born around 1940. Their foreign role models were swank rock and pop singers (the beat groups would come into vogue later in the ‘60s). Therefore no rock groups were formed in Iceland in the wake of rock’s surging popularity. Instead, the rock-crazed kids got to appear on stage with the existing dance bands and sing a few songs. At other times, special shows were staged where up to twenty young singers got to sing a song each. The best of those kids kept at it, and some even went on to release records.

As early as 1956, rock music began to appear on the dance bands programmes, although none of them specialised in the new fad. Gigs were held in the day during weekends, or started early in the evening on weekdays. Like a karaoke of sorts, young guests could come up on stage and sing a tune with the band. This form of concert got very popular, and up and coming singers could gradually overcome their shyness this way. Those who performed best and had the most authentic style were given more opportunities, others dropped out quickly.

Eighteen-year-old Þorsteinn Eggertsson was so convincing in his rock ‘n’ roll fury that Haukur Morthens dubbed him “The Icelandic Elvis.” Þorsteinn kept it real, steered clear of any soppy shit, sticking to rock and roll exclusively while fostering serious lyrical ambitions. Coming from Keflavík, right by the Army base, he had a better grasp of English than most of his peers. Later he was quoted in an interview saying: “The radio signal was bleary back then, and one didn’t hear but a bit of what Elvis was singing. The other kids repeated his lyrics just like parrots, in a pidgin language, which I found disgraceful. Instead, I started making my own lyrics in Icelandic to sing to those rock songs.”

He would later take over vocal duties for the KK Sextet, a gig that lasted six months. Joining the KK Sextet was the ultimate dream for singers at the time. Þorsteinn’s rock fury was unfortunately never captured on record at the time, but throughout the ‘60s and ‘70s he was Iceland’s major rock lyricist, penning some great lyrics, often in deep disdain of the ruling cultural elites.

Siggi Johnnie was another one who “got” the whole rock thing. He sang all around town with various dance bands, and joined the first band to feature only young rock enthusiasts after their original singer, Guðbergur Auðunsson, had left. The band was called Fimm í fullu fjöri (“The Fully Alive Five”), a name that was to be taken as a shot at the old brigade. In 1959, they were the only real rock band in Iceland.

“I booked the band at clubs at the US base,” Siggi says. “At the time, these were the best gigs available and we got paid five times more than we got for gigs in Reykjavík.” The fences surrounding the Miðnesheiði base were a gateway to a different world, one filled with a tantalizingly foreign atmosphere and various unknown pleasures. Besides more money, gigs at the base meant access to all kinds of rare luxuries: American candy, hamburgers and, of course, beer, which for some odd reason that no one could remember had been prohibited in Iceland since 1918 (and would remain so until 1989).

“At this time we mulled over the American forces radio broadcast with a tape recorder,” says Siggi. “When something new came on, we learnt it and were able to play it the next day. I wrote down the lyrics, but I wasn’t fluent in English and really did not have much of a clue what Gene Vincent, Chuck Berry, Little Richard and those guys were singing about. I just wrote down the sounds and tried my best to imitate it. Our American audience didn’t seem to mind that I was basically just sputtering nonsense.”

Banned songs

The Icelandic record industry’s initial attempts with rock were fumbled at best. Pop singers were given slightly “rock-ish” songs to sing; sometimes the only indication of them being of the genre was the word “rock” being repeated throughout the song. The first rock song was Erla Þorsteinsdóttir’s “Vagg og velta” (an unsuccessful attempt to translate “Rock and roll”), a cover of Bill Haley’s “The Saints Rock ‘n’ Roll.” (that being a rockin’ rehash of the standard “When The Saints Come Marching In”). The Icelandic lyrics by Loftur Guðmundsson shocked many, as Loftur recycled verses by Icelandic major poets of yore and “soaked them in frivolity and pure nonsense,” as one of many outraged letters to the editor read: “What is sacred to these people!?!”

The song was banned from radio, and copies of the record were smashed on air. It wasn’t the first to be blacklisted by Icelandic state radio; at least two songs had received that treatment before: “Vorvísa” by revue singer and impersonator Hallbjörg Bjarnadóttir—because it was an old poem by Jón Thoroddsen that Hallbjörg had written a jazzy tune to, and that was absolutely unacceptable, and “Kaupakonan hans Gísla í Gröf” by Haukur Morthens because the lyrics contained a few nonsensical words. Needless to say, the central figures at the state radio station were very conservative at the time, and really protective of Icelandic culture and language.

Erla Þorsteinsdóttir was far from being a rock ‘n’ roller. She was a cute and cosy soft pop singer who barely moved on stage, having just returned from Denmark where she lived for a period and made a name for herself as “The Icelandic Lark.” Shortly after the release of her banned song, Erla went on a tour of Iceland with Haukur Morthens, where she often got scolded by angry audience members for singing the indecent song. The single sold well, however—getting your song banned from radio usually makes for good record sales.

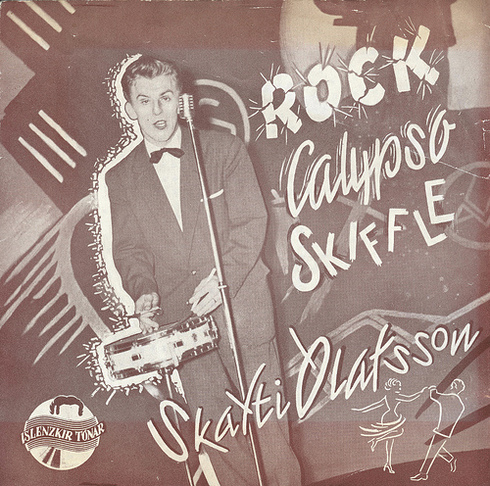

Singer and drummer Skapti Ólafsson was the first to properly nail this new rock thing. He recorded six rock songs between 1957 and 1958 that all sounded pretty convincing. The biggest hit of these was “Allt á floti” (“Everything’s Soaked”)—an Icelandic version of “Water, Water” by the UK’s first rocker, Tommy Steele. This song was yet another that was banned from the radio, presumably because radio personnel thought it included hidden sexual messages. Of course this made for the best publicity possible, and the single sold like crazy. Eventually Skapti was able to buy a refrigerator with the income from the single.

“Just put nylon socks on your heads!”

Yet another young rock dude was the chummy Stefán Jónsson. His first claim to fame was being part of the SAS Trio. The trio did an Icelandic cover version of The Coasters’ “Charlie Brown,” which was released by Stjörnuhljómplötur (“Star Records”), a short-lived branch of Íslenskir tónar that specialised in singles by young singers, some of them seasoned from singing with the dance bands.

As the ‘50s turned into the ‘60s, a new generation of musicians and listeners started gaining ground. The older jazzists gave way to younger dudes who “understood” rock ‘n’ roll. During the summer of 1960, new bands featuring rock-thirsty teenaged boys mushroomed. Rocking dance bands such as Junior, Eron, Uranus and Falcon played wherever and whenever they could, but Plúdó soon became the premier band. The band had to change its name when a silver making company, also named Plúdó, complained. The band chose Lúdó instead, and added “og Stefán,” probably echoing Cliff Richards and the Shadows, who were all the rage at that time. Stefán Jónsson sang for Lúdó og Stefán, and in the early ‘60s they were Iceland’s hottest band.

The band could in part thank their manager Guðlaugur Bergmann for its popularity. He had been one of the main rockers in town and would later become a big shot in the Icelandic fashion world when he opened his breakthrough fashion store Karnabær (named after London’s Carnaby Street). As a band manager, Guðlaugur was very innovative. For instance, he advertised that Lúdó og Stefán would play “Gagarin-rock” (in honour of the Soviet astronaut) and “Horror-rock.” The band had no clue when they read those ads in the papers. When they asked, Guðlaugur answered: “Just try to jam some outer space kind of music!” As for “Horror-rock”— “You just put nylon socks on your heads!” Guðlaugur also took the band into the fashion business by manufacturing special “Plúdó sweaters.” The sweaters (just simple white sweaters with a big black P on the chest) were popular and shifted 2,500 copies in the summer of 1960.

Lúdó og Stefán crossed paths with the hottest new comedy talent in town, Ómar Ragnarsson. He was only eighteen when he started regularly performing shows with an original programme, a unique mix of sketches, impersonations and rock ‘n’ roll.

“I had no role models, Icelandic or foreign,” he says. “Up to then, Danish revue-songs and outdated American songs had been the main features in comedy routines here—it was almost always the same song with different joke-lyrics each time. My programme was based on the latest rock songs, the most popular songs at the time. This was a breakthrough. This was new and fresh. I was the right man at the right time. I was and I am a rocker.

“I am a fan of Chuck Berry and Little Richard. I never thought Elvis was completely true, however.” Lúdó supplied the music to a few early ‘60s singles featuring Ómar Ragnarsson’s tunes, as well as releasing few hits of their own. As the beat bands came crashing in, Lúdó og Stefán quickly became obsolete and eventually split up. They would reform in the ‘70s and release two popular albums of old foreign rock songs with new Icelandic lyrics, most of them written by Þorsteinn Eggertsson. The band kept going far into the 21st century, playing alongside Sigur Rós on a few occasions as well as performing at Sigur Rós’ end of tour party in 2008, where they totally lifted the roof off the house with their eternally cool rock ‘n’ roll music.

—

Over 100 Years Of

Musicians Trying To

Escape The Island

Dr. Gunni On His History Of

Popular Music In Iceland

Words by Haukur S. Magnússon

Hi Dr. Gunni! Congratulations on your new book, ‘Blue Eyed Pop – The History of Popular Music in Iceland’! The title is mostly explanatory, but perhaps you’d be willing to tell us what it’s about, in broad terms?

Oh thank you. Yes, the “History of popular music in Iceland” subtitle explains a lot. This is just the story—as I see it—from Icelanders’ earliest cornball attempts of making “pop” in the 19th century to the crazy growth and prosperity of today, having fostered a variety of big international acts. This is quite the feat for such a dwarfish nation.

My take slants more towards entertainment than academia, and I try to explain the various and changing zeitgeists of the pop scene as we move along. The history of Icelandic pop is full of short stories about people and bands, and they often have a similar storyline that involves folks trying to escape the sameness of the tiny Icelandic scene. Icelandic musicians had been trying this for decades before finally someone succeeded in the ‘80s. The book is full of pictures too, many of which are previously unseen, silly stuff like Björk working at a farm in the early ‘80s—I’d say this is a coffee table book, as well as the first book of this kind—ever!

By popular music, do mean chart-topping music, only? Is there a decided lack of Andhéri and Cranium in the book—or does it also cover less popular, yet rather influential, music?

The chart topping stuff gets its fair share, but we also have lots of what was once called “underground” music. I released a version of this book in Icelandic last year that was three times the size, the “international version” had to be much more explanatory and I focus much more on stuff that is known outside of Iceland. Local heroes like Bubbi Morthens are mentioned of course, but they do not get three chapters here, like they did in the Icelandic version.

NAÏVE ICELANDERS

Indeed, you’ve published two Icelandic language books on the history of Icelandic pop, one in the early ’00s and then the one that came out a year ago. What’s the difference between those two books?

The first one was only about “rock” and with that I could skip all kinds of stuff. The last one was about “pop” so then I had to include everything, as “pop” for me means all “popular music,” whatever that means. You know, both some accordion playing dudes in the early 20th century, the jazz scene in the ‘50s, etc.

What about the book’s title, the Sugarcubes-referencing ‘Blue Eyed Pop’? What’s the story there? Is it just a cool phrase, or is it some sort of statement on your subject matter, Icelandic pop music?

It’s both a cool title and also descriptively of the Icelandic mindset in pop music and what have you. Icelanders are pretty naive in thinking that the world revolves around us and that everybody is interested in us. In Icelandic, the phrase “blue-eyed” means being gullible. And through the decades, pop musicians have been very “blue-eyed” about their possibilities of breaking through to the greater world. Fortunately, we always have more and more artists that manage just that and reinforce our collective belief, thus keeping the passion alive. Am I starting to sound like a tourist brochure here? Sorry, that was not my intention, but unfortunately I often do!

HISTORY REPEATING

Having immersed yourself in the history so much, you must have drawn some conclusions…

Yes, through the history of Icelandic pop, the same story keeps repeating over and over, perhaps with a few minor differences. For instance, the jazz snobs of the ‘50s arguing about music in “The Jazz Paper” are the same types as the Pitchfork-reading indie snobs of today arguing about music on-line. And always, the vast majority of people just want something they can hum to, something that gets them moving on the dancefloor.

What do you believe to be some of the most pivotal moments for Icelandic pop?

Those moments are measured by the release of great records and when Icelandic artists enjoy success abroad. It’s all in the book of course, but for me the five best bands of all times in Iceland are Hljómar (AKA Thor’s Hammer), Fræbbblarnir, Purrkur Pillnikk, The Sugarcubes and Sigur Rós.

Its greatest triumph?

I don’t want to pick one special moment for this, but I guess after our bank collapse a lot of people saw that our success in pop was for real, not some fickle bubble.

And its most sadly lost opportunity?

Songwriter Gunnar Þórðarson (of Hljómar, etc.) should be world famous by now for all of his great songs.

Buy subscriptions, t-shirts and more from our shop right here!