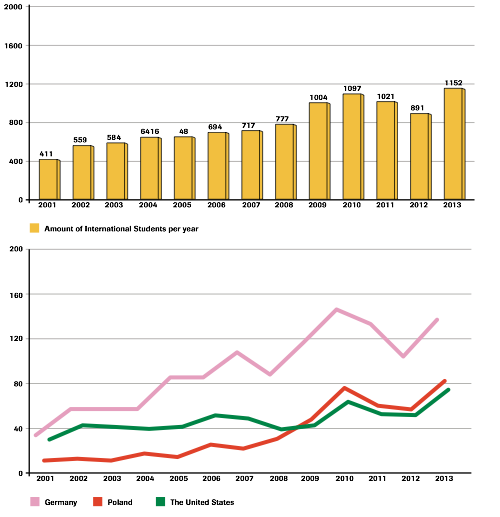

Summer, if it ever really arrived in Iceland this year, is drawing to a close. As the air gets crisper and the days get shorter, school is starting once again. And there are a lot of new faces around the University of Iceland these days. International student enrolment has been on the rise since 2001, when only 411 foreign students were in attendance. As of this year, 8% of the university’s total enrolment, or 1,152 students, are from foreign countries and many of the international students enrolled today are not just spending a semester or two here, but studying in full-time, degree-earning programmes.

The Germans

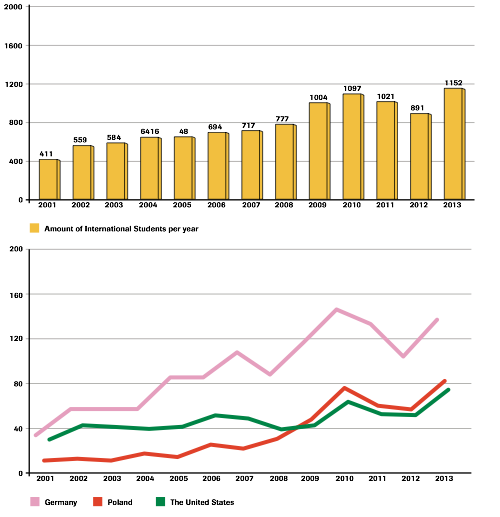

Germany has sent more students to the University of Iceland than any other country since 2002, and a total of 137 German students are enrolled this semester. Poland has the second highest number of foreign students (82), followed by the United States (74), Denmark (64), and France (60). Students from the other Nordic countries are well represented, but many come from further afield: 31 Chinese students are enrolled this year, 34 come from Lithuania, and 33 from Canada.

And the international demographics have also changed a great deal in the last decade or so—several countries which did not enrol any students at the University of Iceland in 2001 now regularly send at least a few students to study in Iceland each year: in 2013, there are three Columbian students, seven students from both Estonia and the Philippines, three Australians, and seventeen students from India.

Studying Icelandic

International students are enrolled at both the undergraduate and graduate levels. According to data from the 2012 academic year, the highest enrolments of foreigners at both levels is, perhaps expectedly, in the School of Humanities, which houses the Icelandic and Comparative Cultural Studies Department. There, 319 international undergrads are enrolled in Icelandic and 40 in the graduate programme, making it the most popular programme amongst international students. The School of Engineering and Natural Sciences also has high international enrolments—there are 103 undergraduates in this school (54 of whom are studying Earth Sciences) and 86 graduate students (37 of whom are studying Life and Environmental Studies).

International students are also found peppered about a variety of other programmes: for undergraduate studies, there are two enrolled in Social Work, one each in Odontology, Food and Nutrition, and Religious Studies, and six in Electrical and Computer Engineering. International graduates are also found in Law (7), Linguistics (25), and Sport, Leisure Studies, and Social Education (2).

But Why On Earth?

Karitas Kvaran, the project manager of the University of Iceland’s International Office, attributes increased international enrolments to a number of factors, not the least of which are economically-based. For one, in the wake of 2008’s economic crash and the devaluation of the Icelandic króna, Iceland is now a much more affordable country for students.

Additionally, the University of Iceland does not charge students tuition, regardless of their nationality (note that there is an annual 60,000 ISK registration fee). Universities in Sweden, Denmark, and Finland, in contrast, have all introduced tuition fees for non-EEA students in the last three years, and have all seen decreased international enrolments as a result. Iceland, along with Norway, has kept its higher education system free for all students, and Karitas believes that many international students who might have attended university in other Nordic countries, are now turning to Iceland instead.

The University of Iceland has long hosted exchange students through programmes such as NordPlus, Erasmus, and ISEP, the International Student Exchange Program. It has also cultivated partnerships with over 450 universities around the world. These partnerships facilitate the enrolment process for international students in Iceland, as well as that of Icelandic students abroad. Some of these affiliations also involve co-sponsored graduate programs, such as the Master’s degree in Viking and Medieval Norse Studies. Students in this programme complete their first year in Iceland and then go to Oslo, Aarhus, or Copenhagen for their next semester of study. These partnerships and collaborations have clearly been attractive incentives for international students. As Karitas points out, there are double the number of foreign exchange students coming into the University of Iceland than there are Icelandic exchange students enrolling in partner universities abroad.

Another factor that may explain the recent boom in international enrolments is, of course, the increased availability of courses offered in languages other than Icelandic. In the past, students who could not speak or read Icelandic had few course options, Karitas says, outside of perhaps a few foreign literature courses taught in the original language (French or German literature, for instance). Now, there are a wide range of options for English-language instruction—both in single courses and also full degree programmes (a quick survey of this year’s academic catalogue shows dozens of courses taught in English, in over 20 different programmes).

Whatever the reason for venturing out to this cold and damp rock in the middle of the North Atlantic, we welcome you, útlendingar, and wish you the best of luck!

The Germans

Germany has sent more students to the University of Iceland than any other country since 2002, and a total of 137 German students are enrolled this semester. Poland has the second highest number of foreign students (82), followed by the United States (74), Denmark (64), and France (60). Students from the other Nordic countries are well represented, but many come from further afield: 31 Chinese students are enrolled this year, 34 come from Lithuania, and 33 from Canada.

And the international demographics have also changed a great deal in the last decade or so—several countries which did not enrol any students at the University of Iceland in 2001 now regularly send at least a few students to study in Iceland each year: in 2013, there are three Columbian students, seven students from both Estonia and the Philippines, three Australians, and seventeen students from India.

Studying Icelandic

International students are enrolled at both the undergraduate and graduate levels. According to data from the 2012 academic year, the highest enrolments of foreigners at both levels is, perhaps expectedly, in the School of Humanities, which houses the Icelandic and Comparative Cultural Studies Department. There, 319 international undergrads are enrolled in Icelandic and 40 in the graduate programme, making it the most popular programme amongst international students. The School of Engineering and Natural Sciences also has high international enrolments—there are 103 undergraduates in this school (54 of whom are studying Earth Sciences) and 86 graduate students (37 of whom are studying Life and Environmental Studies).

International students are also found peppered about a variety of other programmes: for undergraduate studies, there are two enrolled in Social Work, one each in Odontology, Food and Nutrition, and Religious Studies, and six in Electrical and Computer Engineering. International graduates are also found in Law (7), Linguistics (25), and Sport, Leisure Studies, and Social Education (2).

But Why On Earth?

Karitas Kvaran, the project manager of the University of Iceland’s International Office, attributes increased international enrolments to a number of factors, not the least of which are economically-based. For one, in the wake of 2008’s economic crash and the devaluation of the Icelandic króna, Iceland is now a much more affordable country for students.

Additionally, the University of Iceland does not charge students tuition, regardless of their nationality (note that there is an annual 60,000 ISK registration fee). Universities in Sweden, Denmark, and Finland, in contrast, have all introduced tuition fees for non-EEA students in the last three years, and have all seen decreased international enrolments as a result. Iceland, along with Norway, has kept its higher education system free for all students, and Karitas believes that many international students who might have attended university in other Nordic countries, are now turning to Iceland instead.

The University of Iceland has long hosted exchange students through programmes such as NordPlus, Erasmus, and ISEP, the International Student Exchange Program. It has also cultivated partnerships with over 450 universities around the world. These partnerships facilitate the enrolment process for international students in Iceland, as well as that of Icelandic students abroad. Some of these affiliations also involve co-sponsored graduate programs, such as the Master’s degree in Viking and Medieval Norse Studies. Students in this programme complete their first year in Iceland and then go to Oslo, Aarhus, or Copenhagen for their next semester of study. These partnerships and collaborations have clearly been attractive incentives for international students. As Karitas points out, there are double the number of foreign exchange students coming into the University of Iceland than there are Icelandic exchange students enrolling in partner universities abroad.

Another factor that may explain the recent boom in international enrolments is, of course, the increased availability of courses offered in languages other than Icelandic. In the past, students who could not speak or read Icelandic had few course options, Karitas says, outside of perhaps a few foreign literature courses taught in the original language (French or German literature, for instance). Now, there are a wide range of options for English-language instruction—both in single courses and also full degree programmes (a quick survey of this year’s academic catalogue shows dozens of courses taught in English, in over 20 different programmes).

Whatever the reason for venturing out to this cold and damp rock in the middle of the North Atlantic, we welcome you, útlendingar, and wish you the best of luck!

Support The Reykjavík Grapevine!

Buy subscriptions, t-shirts and more from our shop right here!

Buy subscriptions, t-shirts and more from our shop right here!