The founding myth of Iceland goes something like this: A bunch of hardy people from the West coast of Norway escaped the terror—and high taxes—of a king called Harald the Fairhaired. Along the way, they picked up some slaves of Celtic origin—and thus the Icelanders became a poetic race and were saved from the fate of being dull like Norwegians.

Iceland’s Golden and Dark Ages

These people went on to found a true democracy, based upon Alþingi, the oldest parliament in the world. These were proud and noble people, and if they were also Viking raiders, they did their killing in a somewhat endearing fashion—like the warrior-poet Egill Skallagrímsson who always had a joke on his lips when he murdered innocent people.

This Golden Age—the age of the great sagas—ended when the chiefs of the greatest families started fighting amongst themselves in the 13th century. This ended with the ultimate betrayal by a chieftain called Gissur the Earl, who delivered Iceland into the hands of the Norwegian king.

Thus the Dark Ages were ushered in. These lasted for more or less seven hundred years, during which time Iceland was under the reign of first Norwegian and then Danish royalty. They treated us horribly in most ways, erected big and beautiful palaces and churches in Copenhagen—founded on Icelandic wealth—while they shipped boatloads of maggoty food back to the Icelanders.

Is it true?

This is a standard version of Icelandic history, epitomized in text books for schools written by an early twentieth century politician called Jónas Jónsson from Hrifla—Hrifla being a small farm in the north of Iceland, where he was born. Jónas was a man who fervently believed that the fate of the Icelanders and their true culture lay in the countryside, with the peasantry. In the thirties he was a dominating figure in Icelandic politics, he is said to have been asked by the Danish king Christian X:

“Are you still playing at being the little Mussolini?”

The story continues with the independence movement in the 19th century. There we have a group of nationalistic poets and intellectuals saving the country from the grips of foreign colonialists—chief among them Jón Sigurðsson, the national hero, who’s statue stands facing Alþingi, his strong gaze piercing the windows of the parliament building.

Modern historians have questioned many aspects of this story. Possibly the very isolated and inward Icelanders were partly to blame themselves. The isolation might even have been a tool for rich farmers, the ruling class of the country, to oppress the general population.

In fact, the dark ages do not start until much later than the above history would have it. Until the reformation of 1550, the country fared relatively well, even doing good business with English seafarers who traded with the Icelanders. The most horrible time were the 17th and 18th century, when very few ships came to Iceland; this was a period when the Icelanders languished in their mud hut dwellings through the cold and dark of the arctic night. At that time Icelanders were the poorest people of Europe. Volcanic eruptions, pestilence, hunger and cold decimated the population—plans were drawn up to move all the all the residents (well, the 40 thousand who were left) to the heaths of Jutland.

At this time Alþingi had simply become a court of law, where horrible judgements were meted out. Adulterous women were drowned, small time thieves were flogged and had their limbs cut off, sometimes for stealing a piece of rope, alleged sorcerers were burnt at the stake. Over this presided the farmer chiefs who had founded a system of serfdom wherein working people were bound to the farms where they were placed. Their fear was that people of independent mind might move to the seaside, start fishing, and towns would begin to form and thus they would lose their grip on society.

The idea that great wealth was founded upon these people is preposterous. Even if Halldór Laxness says so in his famous Íslandsklukka (Iceland’s Bell), a key work of the late independence movement, Copenhagen was not built with Icelandic money.

NATO ushers in a Soviet-Iceland

Iceland after independence in 1944 was a strange place in many ways. During the war the country became fabulously rich, using the opportunity to sneak away from the Danes—then under German occupation—to found a republic, albeit under the protection of the US military. And, despite Iceland having actually made money from the war, it received its generous share of the Marshall help.

All this money was spent in a few years. This heralded a chapter in Icelandic history where the country can almost be compared to one of the socialist republics of Eastern Europe. Extremely tight currency restrictions were put into place—not to be lifted until the late eighties—food, clothes and building materials were rationed by an all powerful government agency. Even if the country had not suffered any hardships during the war, people stood in long lines to buy necessities.

To the frustration of the Americans, the powerful socialist party managed to make an agreement with the Soviet Union, accepted even by the right wing, stating that the Russians would buy fantastical amounts of Icelandic herring and woollen products in exchange for oil and Russian cars. Far into the eighties the streets of Reykjavik were full of Russian Moskvitsh and Lada automobiles, and even if the oil companies called themselves Esso, Shell and BP, they all sold the same Russian oil from the same Russian tankers.

Beer was not for sale in the country, it was simply banned. So was the import of foreign candy. Some shops even dealt in smuggled boxes of Quality Street—a very sought after luxury item at the time.

The owners of Iceland

The whole system was under strict political control; to get loans in banks or even housing you had to have political contacts. The riches that were to be gained from the US military were divided between cronies of the largest political parties. No wonder the Independence Party, the dominating party in the history of the republic, has been compared to the Mexican ruling party, the strangely named Institutional Revolutionary Party. To get anywhere in society you had to belong to the right party, merit counted for very little.

Icelanders have always believed themselves to be exceptional. A former Prime Minister once famously remarked that normal economic laws did not apply in Iceland. It has been governed accordingly, with the restrictions of the fifties and sixties, the rampant inflation of the seventies and eighties, and then consumer mania in the nineties, culminating in the big bubble that burst in October 2008.

The founding myths are being paraded again, about Gissur the Earl, the so-called “Old Treaty” (Gamli sáttmáli) and Iceland’s loss of independence in 1262. About Jón Sigurðsson and his stand against the Danish government: “We all protest!” (Vér mótmælum allir!). Jón Sigurðsson is being portrayed as a staunch opponent of the European Union—150 years before the fact.

In a sense this is a battle between those who prefer openness and those who are content with isolation—a theme in the real, not the sanitized, history of Iceland. Much of the ruling class and the opinion makers are home grown, they come from the same schools and the same law department, famous for its lack of intellectual curiosity. In their hearts they consider themselves to be the owners of Iceland, much as the farmer chiefs of the dark ages. They fear that joining the EU would undermine their power.

Dealing in deception

In the age of the sagas Icelanders seem to have been wealthy. In recent research this been attributed to thriving commerce between Iceland and Greenland and Europe. Iceland didn’t have much of worth to export, but in Greenland you had furs and tusk. The West of Iceland, where most of the sagas were written, seems to have been a port of trade for Greenlandic goods. Some historians still think that this wealth was based upon dried fish and wool of questionable quality, not products that would fetch a high price in any period, but the former explanation sounds more plausible. To write one saga you have to be able to kill a lot of calves for their skin.

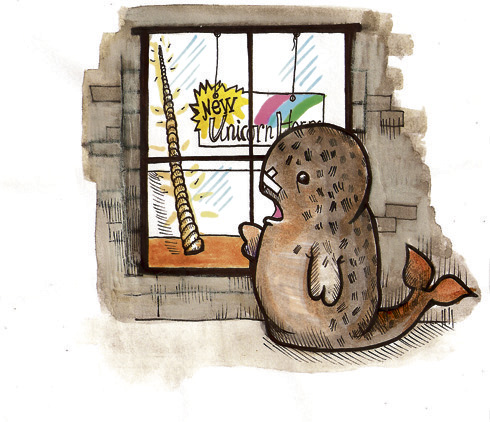

It is even said that the most valuable commodity of all was the tusk of the narwhale, almost two meters in length, sold in Europe as unicorn horns and worth a bishop’s ransom. Those merchants would have been the true forerunners of the venture Vikings of the 21st century. Like them, they would have dealt in deception; because of course, they could not have divulged the true origin of their prized goods.

Buy subscriptions, t-shirts and more from our shop right here!