It was a Saturday much like any other in Greenwich Village, New York. Business as usual on a balmy night in June. An assortment of drag queens, queers and lesbians congregated at the Stonewall Inn while an assortment of New York’s finest proceeded to raid it. Under the usual pretexts, seven plain-clothes officers roughed up the resident fags, before bundling them in the waiting paddy wagon

On this particular hot June night, however, the fags departed from the script and decided to fight back. Amid the confusion and the billy clubs, it was never clearly established who started what. According to riot veteran Craig Rodwell, “it was… a flash of group mass anger,” borne no doubt from being spat on one too many times. Those thrown out on the street began to hurl coins in symbolic derision at the corruption of the police who extorted massive sums of money – “gayola” – from gay establishments by utilising the public morality codes to regulate their scam. The coins were soon followed by rocks and bottles, which were in turn followed by riot police reinforcements. Word soon spread through the village and hundreds of gays and lesbians, black, white and Hispanic, converged on the Stonewall Inn and engaged in running battles with the police late into the night. Things would never be the same.

Before Stonewall

That is not to say that gay solidarity movements did not exist before the events of June 1969.

In his seminal 1983 work, Sexual Politics Sexual Communities, John D’Emilio documents the development of gay culture across America from the turn of the century. How the revolutionary processes of industrialization and urbanization drew ever-increasing numbers from the farms to the factory floors making it easier for gays and lesbians to explore their sexuality. By the mid nineteen twenties a vibrant, if clandestine, gay subculture had grown in San Francisco, New Orleans and New York. In society at large, however, homosexuality remained taboo, and was criminalized in many states across America. Simple displays of affection could lead to arrest and, as D’Emilio documents, even to declare oneself a homosexual could lead to enforced incarceration in a mental institution.

Life was even tougher for lesbians, whose relative lack of economic power and independence curtailed their outlets for sexual expression even more. In this respect, the Second World War was a revolutionary event, temporarily (at least) breaking down the codes of social norms as women flooded into the workplace to replace the absent men. Ironically, it was America’s golden era of post-war prosperity that brought renewed repression as the establishment heavily promoted a stultifying conformity that centred on the nuclear family and a culture of consumption to act as a buttress for the capitalist system against the perceived communist threat. This reached unprecedented heights in the McCarthy era of the 1950s, where homosexuals along with purported communists were hounded from their jobs. A ban on the employment of gays at federal level introduced in this period remained on the statute books until 1975.

It was in this repressive climate that the first gay rights movement was born. Harry Hay, an openly gay, card-carrying communist, founded the Matachine society in 1950 to re-educate lesbians and gay men to see themselves as an oppressed minority. Though Hay remains an immensely important figure in the evolution of gay rights, his organisation ultimately reflected the same conservative prejudices of wider society that they claimed to be fighting. While tacitly accepting their supposed perversions, they tried to ingratiate themselves with the authorities to improve their institutional treatment, an essentially craven tactic that became increasingly at odds with the younger radical gay activists who increasingly took their lead from the emerging black liberation movement of the late 1950s. The events at the Stonewall Inn solidified this radicalism channelling dissent into a bona fide radical movement. For Craig Rodwell, it was “…one of those moments in history, that if you were there, you knew, this is it, this is what we have been waiting for”.

After Stonewall

The legacy of Stonewall is difficult to overestimate. It helped inspire gay rights campaigns across America and the wider world. Indeed the most high profile and successful gay rights organisation in Britain takes its name from the famous inn. Stonewall and its campaigning aftermath was also influential in improving the portrayal of gay people in the mainstream media, particularly Hollywood. Since the inception of the draconian Hays code in 1934, sexual “perversion” along with seduction and prostitution was banished from the screen. Often, it tacitly discouraged filmmakers from even alluding to the love that dared not speak its name. Prominent examples from the 1950s included the cutting of the famously suggestive bathing scene between Lawrence Olivier and Tony Curtis (later restored) in Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus and the removal of the homosexual subtext from the film adaptation of Tennessee Williams classic Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, embodied in the play by Paul Newman’s character.

Even as the sixties progressed and homosexuality began to be tackled less obliquely, villainy victimhood and suffering remained the defining characteristics of gay roles on screen. The burgeoning post-Stonewall gay rights movement tapped into the hitherto closeted gay Hollywood elite, prompting more human treatments of gay characters. This process is, however, far from compete, as gay roles in mainstream productions remain drearily stereotypical, with gay characters often reduced to one-dimensional foils to provide lazy, snickering, humour for a predominantly straight audience.

Two steps forward…

One step back

Significant progress in improving the lot of lesbians and gay men was made in the 1970s, most famously by the legendary Harvey Milk in California, the first openly gay man to be elected to high office in the US (or anywhere else for that matter). Milk attained iconic status in perpetuity for his lead role in the resounding defeat of the Briggs initiative, which sought to enforce the removal of all gay teachers from California public schools, before being assassinated in 1977. Optimism was replaced by despair in the early 1980s, with the onset of the AIDS epidemic and the subsequent right-wing backlash bringing renewed discrimination in the form of travel bans on HIV positive men in the US. The struggle for legislative rights inevitably took a back seat to survival, with precious resources being channelled into awareness and prevention of the killer virus.

Though progress has been hard fought and not without setbacks, the early nineties to the present day have seen a quiet revolution in gay equality reform in Western society. European countries such as Holland have, unsurprisingly, led the way. Perhaps most impressive and surprising have been developments in Spain. Emerging from the grip of a fascist dictatorship as recently as the late seventies, Spain remained deeply religious and stubbornly conservative with regard to gay rights, until one Jose Luis Rodriguez Zapatero acceded to power in 2004, introducing a startlingly radical raft of reforms including gay marriage and adoption rights in the teeth of fierce opposition from the Catholic church and the conservative Partido Popular.

A work in progress

Such impressive progress might lead some to believe that, the still contentious issue of gay marriage aside, the work of the gay rights movement is largely done – in the Western world at least.

However, legality and legislation is one thing, real world experience is quite another. Sobering crime statistics recently released from both the US and the UK bring this very reality into sharp relief.

The Advocate, a leading gay issues magazine, recently reported a 28% increase in anti gay bias killings in the US in 2008, the highest rate since 1999. In the UK, official police statistics have shown an alarming increase in violence towards gay and transgendered people across the country in the last 12 months. Nationally, Scotland Yard statistics reveal a 9% rise in homophobic crime while Greater Manchester police recorded a staggering 63% increase. As Superintendent Gerry Campbell of the Metropolitan police aptly concluded: “Homophobia cannot be considered a thing of the past, it is on the increase”

These statistics underscore the reality that mere legislation is not enough and clearly more must be done in the field of education to counter anti gay attitudes, particularly in young male adults. There are two stark facts that underscore this urgent need.

1. Gay teenagers are three times more likely to contemplate or attempt suicide than their straight counterparts.

2. According to recent research conducted by Stonewall UK, to accuse someone of being gay has become the single most popular school ground slur in Britain today.

The school system remains the key public battleground in the fight against homophobia. It is undoubtedly an incubator of future prejudice and violence, but it equally has the potential to promote awareness, tolerance and inclusiveness. Christian fundamentalists, particularly in the US, have long understood this and have fought tooth and nail to prevent the development of proactive policy to promote inclusiveness in public schools.

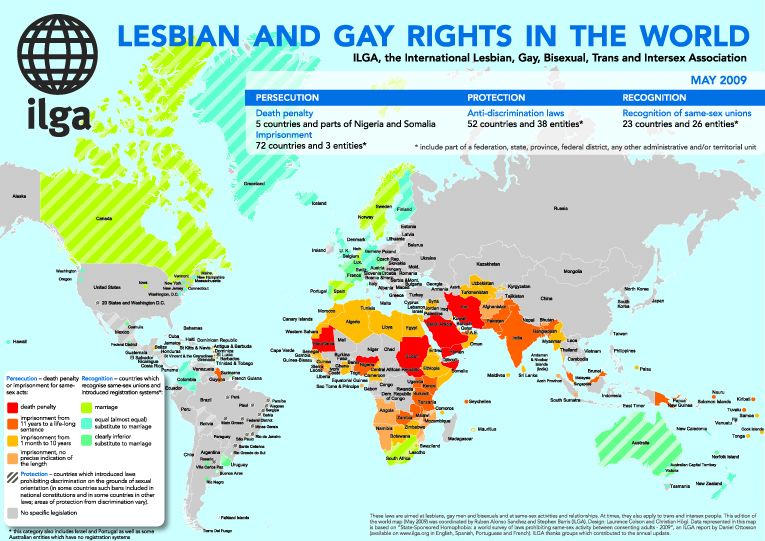

A world of hate

For all the work still to be done and attitudes still to be changed, the major cities of Europe and the US socially, culturally and institutionally are at the vanguard of gay rights progress. As annual gay rights marches across Europe attract mainstream audiences in the millions, it can be easy to forget that in large swathes of the world such freedoms remain the stuff of fantasy. The most virulently anti-gay nations are, undoubtedly, the more fundamentalist Islamic states, such as Iran where homosexuality remains illegal, subject to imprisonment and in many cases torture of the most hideous variety. Another major homophobic black spot is the Russian Federation, embodied by the staunchly anti gay Mayor of Moscow, Yury Luzhkov, who has banned gay pride marches in the city and describes homosexuality as “satanic.” The first ever staging of Eurovision in Russia in May also coincided with the banning and violent suppression of the Slavic gay pride parade that, according to march organizer Nikolai Alexseev, unwittingly did more to publicize gay rights issues in Russia than any other event. “We should give Luzhkov a medal! His violation of our right to protest has given us a remarkable platform.”

As heartening as such victories are, the grim reality remains that across Russia, the former Soviet Republics and even newly minted Eastern European members of the E.U., the (relative) rights and freedoms enjoyed by the gay community in the West are still light years away.

Get up, stand up!

On Saturday August 8, months of dedicated work on costumes, floats and dance routines will come to fruition as the annual Reykjavík Gay Pride parade winds its colourful way down main street Laugavegur. It will be cheered on by residents in the tens of thousands, a testament to the remarkable progress that Iceland has made in its acceptance of the gay community. Amid the pageantry and the play-acting, let us spare a thought for the dykes and drag queens of Greenwich Village, whose courage and defiance helped to make the freedoms that we enjoy today possible.

Reykjavik gay pride celebrations have in recent years become one of the biggest weekends in the Icelandic calendar, drawing crowds comparable to the local Independence day celebrations. For older members of the LGBT community, it is a far cry from the bad old days, when such was the hostility towards openly gay men that some felt compelled to leave the country altogether. In less than twenty years, however, Iceland has seen a revolution in gay rights reform, making the country one of the most progressive nations in the world.

Iceland also has the recent distinction of electing the first ever openly gay prime minister, Jóhanna Sigurðardottir, who took office in February. The following are some of the major legislative milestones on the path to equality

1940 Homosexuality legalized for the first time

1992 Equal age of consent

Anti discriminations laws in employment

1996 Anti discrimination laws in all other areas

“Gay marriage” legalised, referred to as confirmed cohabitation

2006 Joint adoption rights for same sex couples

Legal right to change gender

Legal right to IVF (In vitro fertilization) and surrogacy for all individuals and couples

Parentage for lesbians who undergo IVF

MSMs (“Men who have sex with men”) allowed to donate blood

With such a comprehensive range of rights established, a common (straight) assumption is that there is really nothing left to fight for. This was the question I put to Hafsteinn Þórólfsson, co-founder of St. Styrmir, the Icelandic gay football club. “It is true that we have come a long way in legislative terms, but there is still a lot of work to be done in changing attitudes, particularly in the field sport, which is one area of public life that remains stubbornly homophobic.”

This reality is borne out by the fact that the world of football still awaits it first openly gay player.

“In fact, our team has just returned from competing in the World Outgames in Copenhagen. Those have been instrumental in challenging the absurd stereotype that gays are somehow incapable of playing sports.”

On Saturday, Hafsteinn and his teammates will line up with the dykes on bikes and divas to add yet another dimension to the diversity that is Reykjavik Gay Pride.

SAMPLING Gay life in Iceland

Barbara – Laugavegur 22, 101 Reykjavík

Barbara has been serving up a lively atmosphere for Reykjavík’s gay community (and anybody else who just wants to dance and have a good time) since it opened for business last winter. Located at the site of legendary gay hangout 22 at Laugavegur 22 (actually, despite it’s status as “legendary,” 22 was never “officially gay”), Barbara offers a dance-space at the first level – which is often packed with sweaty bodies – while the second level of the bar offers a place to sit, drink and chat and another in which to smoke.

Jómfrúin – Lækjargötu 4, 101 Reykjavík

Gay operated “Smörrebröd” house serving traditional Danish cuisine. Jómfrúin is a great place for breakfast, brunch, lunch or even a drink on weekend-afternoons, especially during their celebrated summer outdoor jazz-concert series.

Samtökin 78 – Laugavegur 3, 101 Reykjavík – www.samtokin78.is

Iceland’s steadfast gay rights coalition, Samtökin 78, has done an amazing job during the past decades, and continues to do so. Aside from political struggle, Samtökin 78 also runs a gay and lesbian library at its premises, organises social events and provides its members and other gay Icelanders with various invaluable services. Their website features many interesting articles, contact information and a plethora of other things gay travellers to Iceland will find useful.

GayIce – www.gayice.is

GayIce is a very useful. Basically, an intensely informative English-written website that details the various goings-on of the Icelandic gay scene. They also offer chat-forums and a newsletter.

Q – The Queer Student Organization – www.queer.is

Q (formerly: The Coalition of Gay and Lesbian Students) is a relatively young organisation that caters to gay and lesbian university students. It provides them with a means to organise, as well as offering up an often-packed schedule of activities during school season.

MSC Ísland – www.msc.is/ENGLISH.HTM

This is where you learn about MSC Ísland and its schedule, where to go, how to dress and who to meet.

Buy subscriptions, t-shirts and more from our shop right here!