In the United States, drug and alcohol rehab is closely tied to celebrity culture. It’s thought to be for people like Amy Winehouse, who died prematurely due to alcohol intoxication just three years after releasing her hit single “Rehab” in 2007, and Lindsay Lohan, who reportedly wants to open a rehab centre in her name, given her extensive experience in such facilities.

Rehab is not for your average Joe. In fact, only 10% of people in the United States who need treatment for drug and alcohol addiction receive it, compared to 70% for diseases like hypertension, major depression and diabetes, according to a report released by the National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University.

In Iceland, however, the story could not be more different. Iceland’s Centre for Addiction Medicine, SÁÁ, which has been running the nation’s drug and alcohol rehab for the last 36 years, diligently advertises that its practices have touched every family in Iceland through the years.

In fact, the number of Icelanders who have sought rehab treatment for alcohol and drug addiction—12.8% of Iceland’s living male population over the age of 15— is another of Iceland’s per capita world records, according to Gunnar Smári Egilsson, who recently stepped down as SÁÁ’s director. Of Iceland’s alcoholics, he says 70% have sought inpatient treatment at SÁÁ’s Vogur Hospital and 60% of those have been sober for one year or longer, which he thinks must be another world record.

With more than 250 people on the waiting list for Vogur’s 10-day inpatient rehab programme, SÁÁ can’t keep up with the demand. It may be four to six months before those on the waiting list get one of the hospital’s 60 beds, with first-timers being given priority.

Meanwhile, as SÁÁ fundraises to expand its Vogur facilities, countless recovered alcoholics have been sharing their personal stories in the media to raise awareness—just like a cancer survivor might do for cancer treatment in the States. In the last two months, for instance, everyone from the director of a successful ad agency to a respected lawyer and former Supreme Court justice have written columns in Iceland’s daily newspapers, testifying to their successful treatments and encouraging people to donate money to the cause.

So just how did alcohol rehab, something that is fairly uncommon and which often carries a stigma in countries like the United States, become so common and openly accepted in Icelandic society?

A Loophole In The System

The story of alcohol rehabilitation in Iceland begins more than 40 years ago, when attitudes towards alcoholics were anything but favourable and daytime drinking was limited to white-collar drunks and homeless people.

The story of alcohol rehabilitation in Iceland begins more than 40 years ago, when attitudes towards alcoholics were anything but favourable and daytime drinking was limited to white-collar drunks and homeless people.

“At that time, alcoholics were either arrested and transferred to a prison for alcoholics in the countryside, or referred to psychiatric treatment at a mental hospital where they were given hot and cold baths and electroconvulsive therapy,” Gunnar Smári says when I meet him last year at Von (“Hope”), the building that houses SÁÁ’s outpatient centre, Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, social events and more. “The idea that people could recover from alcoholism was a foreign idea.”

Then, in 1975, an Icelander went abroad for treatment at Freeport Hospital in New York. At the time, Icelanders had to go abroad for all kinds of medical procedures that were not available in the country so it was not altogether unusual that the Icelandic Social Insurance Administration agreed to pay for the treatment.

“In two years, 300 Icelanders went to Freeport through this loophole in the system,” Gunnar Smári says. “The most well known bums in town went and were able to recover. This led to a great awakening, and SÁÁ was really founded on a call from the nation to give more people access to this kind of rehabilitation.”

Financially, he says, it also made sense. Treatment was covered by insurance, but patients had to pay their airfare and, although Flugleiðir (now Icelandair) agreed to cut rehab patients a deal, it was not cheap.

Bringing Rehab To Iceland

Among the first to go to Freeport was Hendrik Berndsen, who goes by Binni and runs a flower shop in downtown Reykjavík called Blómaverkstæði Binna. In an article titled “Enginn trúði á þessa róna” (“Nobody Believed In Those Bums”) published in SÁÁ Blaðið, a free fundraising paper delivered to homes, Binni recalls SÁÁ’s formative years when a small group of people took it upon themselves to bring rehab to Icelanders.

“Society looked down on alcoholics, seeing a drinking problem as a weakness rather than a disease. Alcoholics in the mental health system were looked down on, by other patients and not least by themselves,” says Binni, who was admitted 20 times to Iceland’s main psychiatric hospital, Kleppur, before finally seeking help at Freeport and recovering.

When he came back, people could hardly believe their eyes. “People called and asked, ‘what can we do for this one or that one,’” Binni says in the interview, “and so we started shipping people out.” For a year and a half, he says he made 60 trips accompanying alcoholics to Freeport—mostly white-collar drunks like directors, CEOs, MPs, undersecretaries and the director of the Social Insurance Administration—clocking more flight hours than a flight attendant.

Binni and a few others then founded the Freeport Club to support those returning from treatment and to get them into AA meetings. This group then founded SÁÁ in 1977 with the purpose of bringing rehab to Iceland and Binni became its first vice-chair.

After bouncing around between temporary facilities, and even transporting robe-clad patients mid-treatment, as Binni recalls, they set out to build a more permanent home and proved themselves to be not only pioneers in addiction treatment, but also in fundraising.

SÁÁ, Binni says, became the first organisation to get companies in Iceland to raise money for their cause. “We got Frjálst Framtak’s [the company “Free Enterprise’s”] Magnús Hreggviðsson to make calls. We issued bonds that we sent to every home. People could decide how much they wanted to pay and over what time period. Búnaðarbankinn [one of Iceland’s main banks] used this as guarantee on SÁÁ’s loans,” Binni says. “Then the media turned against us. Many journalists were drunks at the time, as you can imagine, and they succeeded in arousing suspicion.”

When that fundraising method failed, SÁÁ came up with another way to sell their bonds. Then director of Sjónvarpið [Icelandic TV]—who Binni describes as “one of us”—had given SÁÁ a primetime slot for a fundraising programme, so Binni and Magnús flew to Los Angeles to convince the stars of ‘Dallas,’ a popular show in Iceland at the time, to make an appearance.

With the help of the Icelandic film producer Sigurjón Sighvatsson, who was studying film in LA, they were more than successful in their mission, secruring not only actors from ‘Dallas,’ but also a number of others, including actress Melissa Gilbert who struggled with drinking and played Laura Ingalls in Little House on the Prairie, another popular show in Iceland at the time.

“This led to a change in the atmosphere and fundraising took off again,” Binni says. “It was like mudwrestling to establish Vogur.”

Checking In At Vogur Hospital

A little more than a year after Vogur opened, Þórarinn Tyrfingsson became its head doctor and treatment coordinator. “Like so many others my age and a bit older, who struggled with alcohol addiction, I drank myself into the field,” he says, chuckling from across his desk at Vogur.

A little more than a year after Vogur opened, Þórarinn Tyrfingsson became its head doctor and treatment coordinator. “Like so many others my age and a bit older, who struggled with alcohol addiction, I drank myself into the field,” he says, chuckling from across his desk at Vogur.

By the time he checked into Vogur, he was working as a general practitioner. Following his treatment, he went on to become an “Icelandic brennivín doctor,” as he calls himself, overseeing what he describes as “10-days of detox and motivation that gives patients hope and assurance that they can find a cure for their evils.”

He emphasises that SÁÁ views alcoholism as a disease and that the treatment at Vogur is evidence-based and all in the hands of doctors. It’s also no accident that the sign greeting people who come for rehab does not just say Vogur, but Sjúkrahúsið Vogur (“Vogur Hospital”), which underlines the fact that the patients are ill. This is also the logic behind requiring all patients to wear pyjamas and robes for the duration of their stay.

A big part of his job for the last 30 years has been to remove the stigma of alcoholism, which he says is important to treatment. “I’ve noticed that it’s easier to treat locals than it is to treat people who come from other cultures, or Icelanders who have lived abroad for some time,” he says, explaining that the way society views alcoholism plays a role in recovery.

“We’ve always tried to put a face on the illness. We’ve gotten highly regarded people, who are celebrities—in the sense that they have recovered and now have a beautiful life—to come forth and talk about their story. That’s how we’ve worked on prejudices against the illness,” he says.

“There’s no stigma of going to rehab and recovering. Ministers have been elected after going to rehab and talking about it openly in their campaigns,” he says. “If you go to rehab and aren’t successful, that’s when there’s a problem.”

He laughs at the idea that people might be over-enthusiastically seeking rehab. “That rarely happens. Patients are very bright. Pregnant women know that they are supposed to go to the maternity ward. People who injure their head know where to go. People with this problem know where they are supposed to go,” he says. “People who come here who don’t have this problem usually have another, more serious problem. I’d be more concerned about them than the alcoholics who come for the right reasons.”

The Addict’s Market

Gunnar Smári, who is also a recovered alcoholic and the former editor and founder of Iceland’s main daily newspaper Fréttablaðið, is equally quick to dismiss the suggestion that SÁÁ, which employs 100 people, is overzealous in any way.

Gunnar Smári, who is also a recovered alcoholic and the former editor and founder of Iceland’s main daily newspaper Fréttablaðið, is equally quick to dismiss the suggestion that SÁÁ, which employs 100 people, is overzealous in any way.

“You have to look at this as a completely divided world. On one side, you have people who experience alcohol as something that lifts spirits during moments of celebration. On the other side, you have people who experience alcohol as the most damning part of their life,” he says. “We want to be recognised as a minority with special needs that are addressed just as the blind get braille and those in wheelchairs get ramps.”

To that end, SÁÁ started a petition called “Betra líf” (“Better Life”) on the organisation’s 35th birthday last October, asking the State to contribute 10% of alcohol taxes—which amount to roughly 11 million ISK per year (nearly 1 million USD)—to their cause. If the proposal—which was delivered to the Minister of Finance in June with 31,000 signatures—goes through, patients would receive an additional 1.1 billion ISK from the State, which currently finances two thirds of SÁÁ’s annual budget of 1.2 billion ISK.

To Gunnar Smári, this is completely logical. “American research suggests that 20% of the population drinks 88% of the alcohol,” he says, extrapolating the data to the Icelandic population. “Of the 20%, 15% are alcoholics who cannot learn to drink and must quit and 5% are heavy drinkers who go out in Reykjavík and drink in a manner that is so crass that it’s hard to differentiate it from the drinking done by alcoholics.”

Given that patients then pay 80% of the alcohol tax while social drinkers pay for 20%, Gunnar Smári reasons that the alcohol tax is a patient tax. “If you think about it, the average alcoholic who comes to Vogur has already paid for the equivalent of something like seven treatments,” he says.

Treatment at Vogur, which is covered by insurance, costs 22,300 ISK [180 USD] per day. “It’s laughable,” Gunnar Smári says. “You can’t find a hotel for that money.” However, more than half of Vogur’s patients then go on to do an additional 28-days of inpatient treatment centred on the principles of AA, and they pay 60,000 ISK of the total cost, 400,000 ISK [roughly 3,300 USD] including the stay at Vogur.

Crusading Onwards

Back at Vogur, Þórarinn tells me the ‘Better Life’ campaign hasn’t been successful in the sense that a government bill doesn’t look like it’s on its way, but he doesn’t seem concerned. “Sometimes you don’t achieve your goals and you have to start again, but some good things still came out of it,” he says. If nothing else, it certainly raised awareness given the large number of people who publicly endorsed SÁÁ as they collected signatures.

Outside, the sound of construction on Vogur’s expansion interrupts the otherwise peaceful surroundings. “A man came the other day and donated 50 million ISK to this expansion project, which costs 200 million with all of the equipment,” Þórarinn says. “We’re like the Metropolitan Opera. We’ve received big gifts like this.”

In the thirty years since Binni flew to Los Angeles to get the ‘Dallas’ stars to help them raise money to build Vogur, it looks like SÁÁ has not lost its knack for fundraising. Last year, it raised 252 million ISK, which is nearly as much as the Icelandic Cancer Society’s 292 million ISK.

Their annual “Álfasala” (“Elf Sale”) has been one of their most important fundraising campaigns since it started in 1990. The white cotton balls with googly eyes that they purchase from China have brought in 430 million ISK over the years. “We don’t have to promote it much,” he says. “Everyone knows it. Now people are trying to steal the idea. Other organisations have other little guys, like the rescue team guy, but we are best known for this.”

Their annual “Álfasala” (“Elf Sale”) has been one of their most important fundraising campaigns since it started in 1990. The white cotton balls with googly eyes that they purchase from China have brought in 430 million ISK over the years. “We don’t have to promote it much,” he says. “Everyone knows it. Now people are trying to steal the idea. Other organisations have other little guys, like the rescue team guy, but we are best known for this.”

And if the media once looked at SÁÁ’s campaigns with suspicion, the unremitting media coverage that they get today suggests that attitudes have changed. The Monday after I met Þórarinn, he appeared on the first show in a weekly series that SÁÁ is airing on ÍNN until Christmas, as part of their “Áfram Vogur” (“Let’s Go, Vogur!”) campaign to fund the expansion of their facilities.

On that show, he continued to drive home the point that all kinds of people come to Vogur for treatment, noting that they recently had three doctors in rehab at the same time. “I’m just waiting for someone from the teenage ward of SÁÁ to become a prime minister,” he says, grinning at the thought. And perhaps when that day comes, SÁÁ will have achieved its ultimate goal of completely de-stigmatising alcoholism and its treatment.

Icelanders don’t drink more than any other nation. The United States, the UK and even Iceland’s Nordic neighbours, Greenland, Denmark and Finland, all drink more per person over the age of 15, according to data provided by The State Wine, Spirit and Tobacco Authority.

When it comes to drinking, Iceland has what is classified as a dry culture as opposed to a wet culture. “In dry cultures,” according to a paper published by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), “alcohol consumption is not as common during everyday activities (e.g., it is less frequently a part of meals) and access to alcohol is more restricted. Abstinence is more common, but when drinking occurs it is more likely to result in intoxication; moreover, wine consumption is less common.”

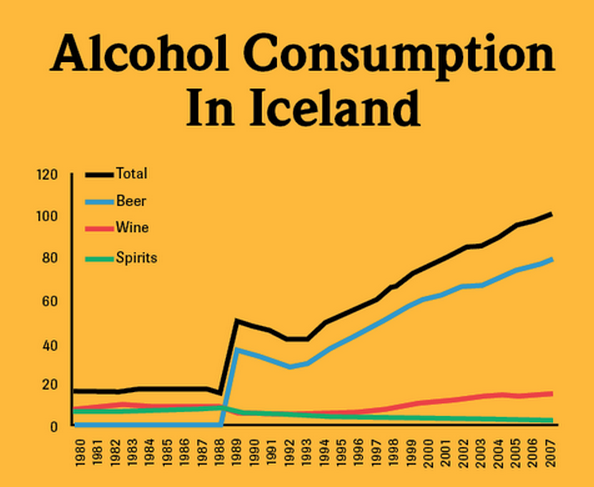

The Icelandic State has a monopoly on the sale of alcohol and sells it at 48 stores called Vínbúð. Vínbúðs around the country sold a total 18,537 litres of alcohol in 2012 with the average patron buying 4.38 litres of alcohol. Of the total alcohol sold, 76.7% was in the form of lager beer, which was notably banned in Iceland until 1989, more than 50 years after prohibition was dropped on all other alcohol.

As the accompanying graph shows, consumption increased dramatically that year and social drinking, which was once frowned upon, has become more accepted over the years. That’s not to say that it has replaced Iceland’s traditional binge drinking culture, which is alive and well on weekend nights in downtown Reykjavík.

Buy subscriptions, t-shirts and more from our shop right here!