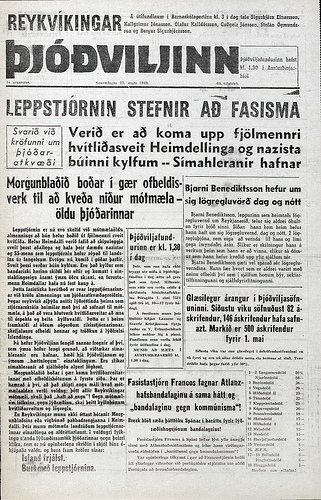

“Wire-tapping has commenced,” stated a front-page headline in socialist newspaper Þjóðviljinn (“The People’s Will”) on March 27, 1949. The paper claimed to possess confirmed intelligence proving extensive tapping of the newspaper’s office phones, as well as the home phones of individuals considered “dangerous” by the coalition government of Sjálfstæðisflokkur, Framsóknarflokkur and Alþýðuflokkur. The reason for said surveillance was reportedly a demonstration scheduled to take place on March 30, when the parliamentary majority would vote in favour of joining the recently established North Atlantic Treaty Organisation. The protest eventually turned into momentous riots on the parliament square, Austurvöllur, where a “furious mob attacked Alþingi,” according to conservative newspaper Morgunblaðið, whereas Þjóðviljinn stated that “treason was perpetrated” inside the parliament while “violent and barbarian attacks against peaceful civilians” took place outside the building.

A LONG AND COMPLICATED STORY

Like every report of state surveillance against Icelandic socialists during the Cold War, these particular accusations were unconfirmed until May 21, 2006, when historian Guðni Th. Jóhannesson presented the results of his research into the matter at the Third Icelandic History Forum, and more extensively in his book ʻÓvinir ríkisinsʼ (“Enemies Of The State”) later that year.

In an introduction to the book, Guðni explains that in 2003, while studying history in the UK, his attention was brought to a few documents at The National Archives in Britain—the secrecy of which had just been lifted—mentioning a systematic gathering of information about Icelandic communists. In the archives of former US President Dwight Eisenhower, he furthermore stumbled upon documents regarding “internal security in Iceland,” which talked about a card index of “communists and their supporters.” This lead Guðni on a quest for bulletproof evidence, as well as vocal testimonies by people possibly involved in the matter—communists and establishment figures alike.

To shorten and simplify a long and complicated story, he finally managed—via the National Archives of Iceland—to acquire theretofore inaccessible documents from the then dissolved Criminal Court of Reykjavík. The documents confirmed that 32 homes of army-base opponents and socialists—some of whom had been parliamentarians at the time—had indeed been tapped, as well as socialist parties and newspapers, trade unions, and various political and cultural associations. Guðni was able to put his finger on six confirmed examples of this, during the period from the above-mentioned NATO conflict in 1949 to a NATO foreign affairs ministerial meeting in Reykjavík in June 1968. Among other occasions was the 1951 visit of Dwight D. Eisenhower—then Supreme Commander of NATO and later US President—and that of then US Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1963.

As no information collected by the wire-taps was ever used as evidence in court, many wondered what sort of information the authorities gained by the acts of surveillance, to which Guðni replied at the History Forum: “Most likely, we will never get to know anything about that. All documents concerning these police operations were apparently eliminated no later than in 1977.” This elimination was quite a spectacle indeed, as according to historian Þór Whitehead, most of the documents were burned to ashes in an oil barrel just outside Reykjavík by the summer cabin of police chief Sigurjón Sigurðsson, who saw the bonfire as a necessary step on his way to a post at Iceland’s Supreme Court.

NO APOLOGIES

NO APOLOGIES

The 2006 revelation immediately brought forth strong responses that—not surprisingly—pretty much followed the same old Cold War lines. Former socialist MP Ragnar Arnalds called the affair a scandal, and told newspaper Fréttablaðið that he believed the information presented by the historian only to be the tip of the Iceberg. Interviewed by Morgunblaðið, Ragnar referred to the tapping as “political espionage” and “an attack on democracy and parliamentary government.” Morgunblaðið’s editor Styrmir Gunnarsson, however, justified the operations, stating that in view of the political situation back then, “it’s actually remarkable that wire-tapping wasn’t used more extensively.”

Among the main arguments of those justifying the espionage—one of them being Björn Bjarnason, then-Minister of Justice—was that it had been legally executed, i.e. by a court ruling, and due to a considerable threat to state security. But as another former socialist MP, Kjartan Ólafsson, noted in a Morgunblaðið article in May 2008, the requests sent to the judges by the Minister of Justice—who usually was Björn’s father Bjarni Benediktsson—didn’t really include any well-grounded reasoning, save some vague mentioning of potential risk of turbulence. Additionally, only in two out of the six mentioned incidents were the requests supported by actual paragraphs of law.

At the end of his article, parallel to which the names of those spied upon were published for the first time, Kjartan called for an official apology from the Iceland state, an idea supported by many on the left. Björn Bjarnason, however, defended his father’s inheritance, stating that judiciary authorities should never apologise for a judge’s verdict. Referring to collapse of the Soviet Union, Björn concluded by locating himself—and his political brothers in arms—on the side of what he called the “verdict of history,” maintaining that “the Icelandic State doesn’t have to apologise to anybody because of this verdict.”

—

This article is part of our issue 10 feature, which spotlights the ongoing, interconnected saga of WikiLeaks, IMMI and the rise of the surveillance state.

Read our interview with former WikiLeaks volunteer/FBI informant “Siggi the Hacker” here.

Read WikiLeaks spokesperson Kristinn Hrafnsson’s response here.

Read informant Adrian Lamo’s comments on the case of Siggi here.

Read about the US’ attempts to gather intelligence on WikiLeaks head Julian Assange by spying on Icelanders (including an MP) here.

Read about the dead or dying dream of Iceland as “whistleblower haven” here.

Buy subscriptions, t-shirts and more from our shop right here!