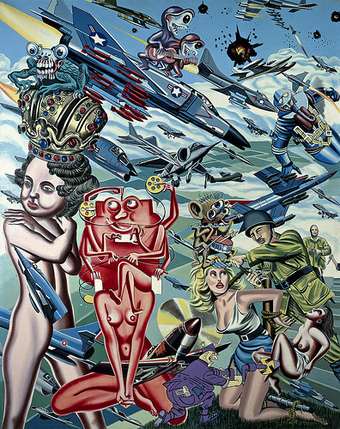

An entire cast of grotesque, comic figures watches us as we cross the room: exaggerated nudes in mock classical pose; portraits of misshapen Picasso-esque faces; towering, iconic statesmen depicted as cartoon baddies.

It’s Friday morning at the Reykjavík Art Museum. A handful of prints are waiting to be framed as the finishing touches are put on the gallery’s newest exhibition, ‘Erró—Graphic Art 1949-2009.’

Guðmundur Guðmundsson, who was born in a fishing village on the north-west coast of Iceland but is today world-renowned by his nom de plume Erró, gazes at every picture with nostalgic recollection in his pale, elderly eyes.

There is only one day to go until the Mayor welcomes a host of guests to the museum to fete Iceland’s legendary old painter for the official opening of a new retrospective showcase of his graphic art, comprising works from the late 1940s to almost the present day.

“I’ve been back in Iceland for three days, and I’m only in Reykjavík until Sunday,” he explains with a grandfatherly smile. “Tomorrow this exhibition opens. And then on Sunday I’m going back to Paris for another exhibition. Then later in September I’ll be going to Copenhagen.”

Any time he returns to Iceland, the red carpet is invariably rolled out. Erró stands today as perhaps the most renowned living artist the country has produced. His work is proudly on display the world over, from New York to the Far East; he counts as his friends some of the most famous artistic names from across Europe and America. I am his first appointment of the morning; the rest of the day, journalists and photographers from the national media will have their allotted time with him too.

This exhibition has been three years in the making, curated by Danielle Kvaran, project manager of the museum’s vast Erró Collection who has researched and collated the entire breadth of his graphic work.

The works we pass by all bear witness to his international acclaim. Collages he was asked to produce for the 1984 football World Cup in Spain and again for the 1992 Barcelona Olympics stand tall—mural-like paintings that draw together on the same canvas an array of faces: athletes, crowds and performers in Castilian hues of red and gold.

Further along are some of the collages he was commissioned to produce by the City of Lille, telling the story of the northern French town through a series of vast, colourful, comic-book style paintings which weave a narrative from Charlemagne to Napoleon and all the way to the advent of the TGV. To this day the originals hang in Lille’s city hall—one of the many venues across the world where Erró’s distinctive hues and shapes can be seen.

STILL GOING STRONG

Only just turned eighty, he walks tall, albeit now rather slowly. He is suited, but tieless—not surprising, even in ripe age, given the irreverent streak that runs through his whole body of work. But though he may have passed the age at which most men draw their pensions, his schedule remains as dauntless as it did when he was a young Nordic radical shocking the sensibilities of the art dealers and critics in fifties Florence and Paris.

He speaks with a voice that has grown gravelly. He is at that stage of his life, that second childhood, when he is all too easily distracted by whatever catches his eye and provokes a memory of a name or a face. As we sit down in the museum’s ground floor library, I ask him how he has spent his short time back in Iceland, before suddenly a large coffee-table book about some Asian artist catches his eye. “I know this artist, he’s a friend of mine,” he murmurs, flicking through the pages, candidly passing choice remarks about the other artist’s wife.

But when he speaks of his life story, the places he has seen and the iconic people he has met and befriended, he remembers and can recount it all like a worldly, wizened man sharing his old stories: his youth spent on the farm; his schooling across Europe’s cultural capitals; his friends Fernando Botero, Jean-Jacques Lebel, and the New York pop artists.

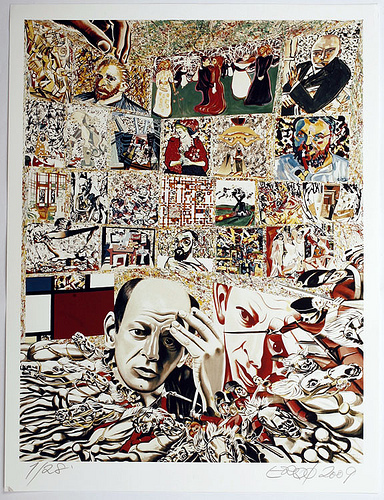

The Hafnarhús exhibition is a tribute to the Reykjavík Art Museum’s old friend in his octogenarian year. It arranges by graphic technique over a hundred works he has donated through the years, offering a broad-brush overview of his oeuvre, comprising stamp prints, linocuts, woodcuts, lithographs, silkscreen prints and digital images.

It begins with some of the earliest prints he made whilst in his schooling, using potato stamps and linocuts of the kind typically now used to teach youngsters about art. Whilst tracing the development of his work through his artistic formative years, the centrepieces of the exhibition remain the collages he created using mass-produced images (adverts, press cuttings, magazine photographs among many). The graphic works in this exhibition were produced by printers who would use photomechanical processes to reproduce his original collages. “The collages are the originals to me, and the paintings are the copies,” he explains. Erró’s role then was largely to choose or apply the colour mix for the final reproductions. He would nonetheless oversee the printing operation, signing off on every one, authenticating each reproduced work with his signature.

The result is a vivid, garish burst of colour from every wall, telling the story of how his art has progressed from his early student days at Reykjavík’s Iceland College of Arts and Crafts (now the Iceland Academy of the Arts), through his studies which took him to Norway and then to Italy, before he settled variously in Paris and New York.

GLOBAL INFLUENCE

He was born in Ólafsvík, a humble village on the Snæfellsnes peninsula, but moved at a young age to Kirkjubæjarklaustur in South Iceland where he lived until he began studies in Reykjavík at age 14. His early days stand in marked contrast to the cosmopolitan, globetrotting life he has long enjoyed. “There is a big farm close to a glacier,” he says, gazing out the window. “I worked in the slaughterhouse. They used to knock out 35,000 sheep there every autumn—it was a massacre.”

Still he remembers it fondly: indeed on returning to Iceland this week, Kirkjubæjarklaustur was his first port of call, visiting his old home. “My biggest pleasure is always going back to the farm and seeing my half-brothers and sisters.” Of course the village of his childhood has seen its own dramatic changes: “The slaughterhouse is now a hotel!” he says, laughing. “We were looking round and one of my brothers was saying, ‘Oh! You remember all the blood here? Oh and here they kept all the carcasses!’ I don’t know what the people staying there now must have thought.”

And it was here that his childhood fascination with visual art was galvanized. “Lots of people came to study the geology and the volcanoes, and stayed on the farm. So they’d send back gifts. When I was ten, someone sent a catalogue from the Museum of Modern Art in New York—and I loved it.”

He remembers clearly the painting that caught his eye most powerfully: ‘Hide And Seek’ by Russian-born Pavel Tchelitchew, in which a girl is seen from behind entering what Erró describes as “a kind of dream world,” a fantastical and faintly threatening collage of ghoulish faces and dismembered limbs painted in monstrous green and blood-red hues.

Looking at the vast, complex collages that adorn the walls at Hafnarhús, it is clear to see what an impact this moment has had on everything that has come from Erró’s hand and his artistic eye ever since. His most iconic works begin with a sketch or a collage, upon which he gathers images that form some kind of narrative. “I start immediately by collecting,” he says, describing his work method. “I need a lot of material for big paintings, so I have many drawers in my studio, each one for different subjects. I have one drawer filled with pictures I’ve collected about the worst things you can imagine: violence, blood, dismembered bodies.”

His artistry is curatorial: he has described himself famously as a reporter in a vast bureau that collects every image in the world; his job is to synthesise all these images and tell a story. “We take in so much information every day, so many images” he explains. “We can’t escape from that. The world changes very quickly, and things happen fast. I’m interested in nailing down big global events—like Vietnam or Afghanistan. I want to capture those moments, and criticise.”

MODEST BEGINNINGS

Erró’s own life story is as globalised as the world his works are inevitably influenced by. “I had a very open-minded family who were happy for me to go to art school in Reykjavík, where my aunt and grandmother lived.”

It was not an easy apprenticeship. “I was worried about my profession, so I eventually moved from art school to work in the teachers’ department. I thought that if I couldn’t make money with my painting, then I would become an art teacher instead.”

It was not long though before he would leave Reykjavík. “Artists here were supposed to go to Copenhagen for art school, but I went to Oslo because I wanted to ski and go mountain-climbing,” he says playfully.

When he went on to travel to Italy, he quickly acquired a reputation as a rather different figure to the creatives with which the artistic circles were familiar. “I ended up in Florence and got into the academy there quite fast. I couldn’t take it in a way because they were all very smart and well-dressed. They painted wearing their ties and fine shoes—like they were working in a bank.”

The off-beat young Erró was never going to be fully embraced within the cloistered artistic scenes across Europe in the fifties and sixties. When he moved to Paris, he found that making a name as an artist was extremely difficult: “Everything was closed. If you went into the studios, all the paintings were turned around so you couldn’t see them. I went to meet dealers and they would throw me out. I was a joke to them, drawing wild pictures and talking about horrible Nordic artists like Munch!”

He found the United States a much more welcoming place. “I lived in New York through the winters in the sixties. In America everything was open: the artists were friendly, like the American people themselves. That’s where I became friends with the pop artists.” James Rosenquist in particular he remembers fondly, realising sadly: “He is the only one left. All the rest have died.” Erró speaks grandly of him as “the biggest American artist, because he’s pure American—had no influence from the rest.” Yet he distances himself from the likes of Warhol or Lichtenstein: “Very often I’ve been squeezed in with them, but I don’t know why.”

POLITICAL ART

Critics associate Erró with the narrative figuration movement, often characterised as a European counterpart of the quintessentially American Pop Art. It had its roots in Paris, which goes some way to explaining why he stayed in such a cloistered environment, one which seemed to restrict radical outsiders like him. “When I arrived in Paris I felt things were going to happen there. Slowly the narrative figuration came in, and I became part of the group. There were about six or seven of us making similar work, like Bernard Rancillac and Hervé Télémaque.”

Like the pop artists, their work called upon contemporary society, its images and objects. Advertisements, comics, films and photographs were all appropriated as motifs, along with concepts and forms from art history. In his paintings, Erró has never been afraid to display an aggressive political bite: juxtaposing socialist-realist renders of China’s Chairman Mao and famous bastions of Western culture like the Paris Opera’s Palais Garnier; a news clipping drawing of Nelson Mandela behind bars held up before a still of a smiling Bugs Bunny indulging in his spaghetti bolognese.

The Cold War and the divide between east and west that has marked so much of his productive life infiltrate his work. Some of these paintings, he tells me, are now being used to educate a whole new generation about world history. “A great pleasure for me,” he says now, “is that paintings of mine are being used in school books. Partly because I get the royalties! But not just for that of course.”

Today, however, he sees money as the root of the world’s problems: “Money is dominating the world. Everyone thinks about it and everyone wants to be rich. It’s the pain in the arse really,” he says brutally. “I thought it would stay in America, but now it dominates the world.”

He admits that he too enjoys a privileged life. “If you put everything together then I’m rich. I’ve been very lucky,” he says, telling me about his houses in Thailand and Spain, and the Parisian studios he has worked in—and where he continues to paint new works.

And though his visits home are only fleeting, Iceland continues to celebrate him. As we part, he invites me to the launch of the exhibition the next day—“You don’t have to wear a tie,” he adds. When the retrospective is at long last declared open Mayor Jón Gnarr presents Erró with an honorary citizenship of Reykjavík, making the artist only the fourth individual to be bestowed with the honour since 1961.

Whilst he is in town he also takes time to award another artist Ósk Vilhjálmsdóttir with money from the fund he set up in his aunt’s name to promote female artists. “There is a lot of talent in Iceland,” he concludes, reflecting on the arts scene in Reykjavík. “But I think they may be lacking stimulation. We don’t have enough art galleries here, and the ones we do have are having problems surviving. They need much more support.”

The Erró Collection in the vaults at Reykjavík Art Museum today comprises more than 4,000 works of art donated over more than two decades: paintings, watercolours, sculptures, as well as the graphic works on display in this year-long exhibition. With his eye-catching, explosive work on the walls at Hafnarhús, Erró continues to play his part in stimulating another generation of Icelandic artists striving to take on the world.

—

CURRICULUM VITAE: ERRÓ

Age: 80

Early Days: Erró worked in the slaughterhouse in Kirkjubæjaklaustur. He was inspired to pursue his art after seeing the paintings in a MOMA catalogue sent to his family by one of the many foreign guests who stayed with them on visits to Iceland.

Nordic Education: Trained in Reykjavík before moving to Oslo. Enrolled in the Painting Department at the Icelandic College of Arts and Crafts, but was persuaded to train to be an art teacher. Taught by Valgerður Briem, in whose classes he practised sketching, paper-cutting techniques, and created drawings that had a strong influence on his later work. In Oslo he studied engraving at the School of Decorative and Industrial Art and learnt about life-drawings, under the tutelage of influential figurative painters.

On The Continent: Headed to Florence in 1954 where he enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts. Armed with a sketchbook, he would visit the Palatine and Uffizi Galleries, copying the works of the old masters. He moved on to Ravenna in 1955 after discovering mosaic art being pioneered there.

Global Figure: Opened his first solo exhibition back in Iceland at the Reykjavík Artists’ House in ’57. Subsequently settling in Paris in 1958, he worked closely with friends Jean-Jacques Lebel and Roberto Matta, themselves renowned for their vast, complex and colourful paintings. Became part of the narrative figuration school, the European counterpart of the largely American Pop Art trend.

Back Home: Now regarded as one of Iceland’s greatest artists, he remains vaunted by the city where he first trained. In 1989 he presented the City of Reykjavík with a large collection of works from his entire career back to his childhood. The Erró Collection in permanent residence at Hafnarhús consists of over 4,000 pieces. As well as the fund he sponsors for female artists, he was back home in Kirkjubæjarklaustur last week where locals and family are aiming to raise funds to build a cultural centre in his honour.

—

COPY AND PASTE?

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Erró has been no stranger to controversy. He gained notoriety in 2010 when he was accused of plagiarism by British comic book artist Brian Bolland. After attracting the attention of artists of every kind for his shameless appropriation of previously published images to produce his many collages, Bolland visited Paris’s Pompidou Centre where Erró’s work was on display. In a lengthy open letter to Erró—“or Mr. Gudmundur if you prefer”—Bolland blasts the Icelander for plagiarising his cover of 1995 comic strip Tank Girl. Seeing his Tank Girl on a poster in prominent view in the gift shop window where it was on sale for 600 euros, Bolland wrote: “It consisted of a badly copied version of my work and, where the original logo had been, a group of figures presumably taken from Maoist Social Realism.” The story did the rounds online until Erró’s agent e-mailed Bolland, telling him this edition ‘Tank’ would no longer be sold: “We have made 20 copies, we sold three copies, we have given 5 copies to Mr. ERRO. We’ll give him the 12 remaining copies.”

—

FIVE ERRÓ PICKS

by Danielle Kvaran

‘The Background Of Pollock’

(1966–1967)

(Centre Pompidou, Musée national d‘art moderne,

Paris)

The Background of Pollock, 1966-1967, glycerophtalic paint on canvas,

260 x 200 cm. FNAC, Ministère de la culture. Centre Pompidou, Musée

national d‘art moderne, Paris.

This is one of Erró’s most important portrait paintings, really a novel and original method of relaying the subject’s story. Again Erró cuts together different times and spaces, connecting Pollock’s artistic premises—expressionism with Van Gogh and Munch at the helm—furthermore granting us an insight by clashing two portraits of Pollock in two different colours, in Pollock’s subconscious. Pollock was very preoccupied with the notion that art should be spontaneous and that it should flow from the subconscious without restraint. In this piece, Erró manages to tell Pollock’s artistic story.

‘Foodscape’ (1964)

(Moderna Museet, Stockholm)

Foodscape, 1964, glycerophtalic paint on canvas, 300 x 200 cm. Moderna museet, Stockholm.

This is the first of the ‘scape’ paintings, where Erró depicts a multitude of similar things. It is a visual meditation on the excessiveness of society’s consumption habits, but first and foremost an original composition that has marked Erró a special place within pop art. It is also fun to keep in mind that Erró himself consumed all the food he portrays in the piece.

‘New Jersey’ (1979)

(Listasafn Reykjavíkur, Reykjavík)

New Jersey, 1979, oil on canvas, 90 x 99 cm.

Reykjavik Art Museum, Reykjavik.

The series of pictures on Mao travelling the world is a product of its time regarding the politics. But the work’s artistic value lies in how Erró, using his collage technique, can cut together different times and realities. This series was a “fiction” that invoked hope and warmth in the hearts of many, or induced a great terror. Furthermore, the work well describes the artist’s witty humour. As Erró himself remarked: “Mao only once went outside of China’s borders, to Moscow. I sent him on a trip around the world. I took him to Venice, Paris, New York. I made him a great traveller.”

‘The World today’ from the series “Maybe later” (2011)

(Listasafn Reykjavíkur, Reykjavík)

The World today, 2011, glycerophtalic paint on canvas, 99 x 70 cm.

Reykjavik Art Museum, Reykjavik.

This is a painting that Erró recently donated to the Reykjavík Art Museum, along with the collage it is based on. By contrasting a few different photos Erró manages, like he often does, to create a strong, visual piece that consists of humour and social critique.

‘The Queen Of Speed’ (1970)

(Private collection, Paris)

The Queen of speed, 1970, glycerophtalic paint on canvas, 162 x 130 cm. Private collection, Paris.

This has clear origins in the collage technique, which allows Erró to create a very original storytelling method through the medium of painting. This painting isn’t one tableaux or linear narrative; Erró spreads images and fragments over the picture plane, in a very dynamic manner in this case, without resorting to a hierarchy of objects or images. The viewer controls and steers the reading process by the meanings she places in every image or fragment. In a certain way, the viewer is floating in a dreamlike world as he slides from one field of meaning to another. This narrative method instils in the piece a plethora of interpretative possibilities.

Buy subscriptions, t-shirts and more from our shop right here!