We meet at Café Babalú, one of Reykjavík’s cosier coffee shops. Full of old furniture and cluttered with books and kitsch ornaments, it seems like the perfect place to meet the legendary Rax—not because he’s old, but because over the past 30 years he’s become such a familiar figure to Icelanders that in many households he is almost thought of as a favourite uncle.

Rax is renowned in Iceland for embarking on solo journeys that readers sometimes get a glimpse of through “Morgunblaðið’s” pages, where he has often displayed otherworldly images of the North—gorgeous, composed photos that often tell a story all on their own, with little or no text to accompany them.

But despite his celebrated status, most Icelanders know little of Rax except what they can glean through his photography and documentaries. He prefers to stay out of the spotlight, letting his work speak for itself. “I hardly know who Rax is myself, because in a way, I am two men,” Ragnar Axelsson—Rax—says, grinning and pointing over his shoulder at his invisible other self. “He’s a pretty good friend of mine, but I often feel as if he’s somebody else. Sometimes I can’t stand him, but I know deep down that he’s a pretty nice guy.”

As we walk up the stairs to Babalú, Rax mentions that he’s going sea bathing right after the interview. “I’ve recently started doing that, and love it. It awakens your entire body,” he says, explaining that after a snowmobiling accident in Greenland, he experienced back pain and felt his left arm getting slightly limp. “After I started going into the sea, it got better. I can’t explain it, but it’s as if a power rushes out to your limbs.”

We sit down opposite one another with our lattes, which Rax absolutely insists on paying for, reasoning that he might be ‘the last gentleman in Iceland.’ He makes himself comfortable, slinging his legs over one arm of the worn-out armchair, before leaning back to tell me about his childhood summers at Kvísker, a farm in the remote Öræfi region in East Iceland. There he helped the farmers—brothers renowned in Iceland for their scientific documentation of the area—measuring the ice, counting birds, collecting bugs, flies and plants, and documenting for the sake of natural history. All the while, Rax was, of course, also skulking around with his trusty Leica.

“I was always looking at the birds, watching them flying overhead. I could lie on the ground and watch them for three or four hours straight. I became obsessed with photographing them, as well as the people—the characters in the area. But I was extremely shy; I snapped a photo when no one was looking and was terribly ashamed of it. I guess that still lingers within me.”

His shyness is perhaps slightly noticeable in the way he speaks during our conversation. Despite his friendly demeanour, he seems a little bit on edge, suddenly bursting out with what he wants to say at intervals. Sometimes it’s borderline incoherent, as if he puts more effort into turning his thoughts into words than forming sentences with a clear beginning and end.

But maybe he just doesn’t have a way with words the way he has with pictures. “I didn’t know it for the longest time, but I’m dyslexic, so I automatically think about everything in images. I see pictures in everything,” he explains. Still, he has never allowed the condition to hold him back and he reads a lot, especially scientific stuff, which he’s had an active interest in since his childhood.

A Restless Family Man

His obsession with birds sparked an interest in being able to fly on his own, leading him to train as a pilot when he reached adulthood. At that time, he says there were hardly any jobs for pilots in Iceland, and what jobs there were didn’t pay particularly well. With a young daughter to take care of, he started an apprenticeship as a photographer and got a job at “Morgunblaðið.”

“I trained with photographer Ingibjörg Kaldal whose father, Jón Kaldal, was Iceland’s greatest portrait photographer. I learnt a lot from studying his work. But Ingibjörg closed down her studio before I finished, so I don’t have any certificate,” he says.

Upon discovering that Rax is a family man with three children and four grandchildren, I confess my surprise, as the image of him that I’d constructed through his published work was of an independent loner who takes long, solo journeys to the Arctic to capture the right shot, a man too absorbed in his calling to maintain steady relationships with other people.

“Rax is a bit of a loner, and he’s often absent minded, but he’s very focused when he’s working,” he says, speaking of himself in the third person. “He can’t stand to lose, so he never gives up. If he has to catch something on film, he won’t stop ‘til he has it. That’s how focused he is.”

Nonetheless, it is surprising to learn that someone who travels as much and as far as Rax does, often putting himself in danger, manages to maintain a family life back home. “I have calmed down a bit,” he says, “but I used to be extremely restless—I can’t really understand why my wife didn’t throw me out long time ago!” On his early expeditions, he would sometimes be away for weeks with no means of contacting his loved ones to at least confirm that he was alive.

“I know I worried my family, and I feel guilty about that. I’ve been trying to make amends, but still, I wouldn’t have achieved what I have if I hadn’t behaved like that.”

Protected By An Invisible Force

Rax still maintains a day job at “Morgunblaðið,” a job he says he still enjoys, although it has changed through the years. “Photographers don’t go on journeys as much as they used to, which is a shame,” he says with a hint of sadness.

“I was always very keen on going to Greenland. I was fascinated by the heroic adventure stories I had read about the Arctic explorers. They were such cool guys and I always wanted to be like them. So I went to Greenland for the first time in 1979, but it was a bit of a disappointment. I went to Kulusuk, and I only really saw drunk people there, no heroes. But then I reached other places in Greenland and saw how grand and beautiful these people were, and when they’re out on the ice, under tough circumstances, they’re so incredible that they make James Bond look like a total wimp! That’s when I can’t help but be proud of knowing them,” Rax tells me.

“One of my friends there, a bear hunter, is so magnificent. I sometimes just sit on the sled and watch him, watch his eyes and the way he carries himself out there on the ice. He’s vigilant about everything; he knows what’s going on around him in a way that an ordinary man couldn’t understand. He sees the weather; he’s just amazing.”

Rax has travelled to Greenland at least once a year ever since that first trip, staying 4–5 weeks each time, travelling far and wide, snapping photos. “Greenland is like a magnet, it pulls you in. Sometimes, I’ll return with frostbite and feeling exhausted, promising myself I’ll never go back, but within a few days, I’ll be longing for it again. There’s something magnificent about that place.”

He admits having sometimes gotten into such dangerous circumstances there that he had to rely on his friends, the hunters, to save him.

“I’ve been caught in crazy weather, jumping from one ice floe onto another as the ice breaks. I thought it was awesome fun at the time, but afterwards I realised that perhaps it wasn’t very clever of me,” Rax jokingly frowns. “I just didn’t want to miss the opportunity for a great photo, that’s how competitive I am. Somehow, I always manage to feel safe—I never get scared until afterwards. You grow to understand that the nature is your friend, as long as you don’t defy it too much.”

Rax’s death-defying behaviour started at an early age. As a little boy visiting his grandparents in the hamlet of Djúpivogur in East Iceland, he and his cousins played underneath the cliffs close to his grandparents’ house. “No one dared to let their children play there except my grandmother. She could see hidden people, and she told me that I’d be all right there, since the hidden people would look after me. And I was comfortable being there. I can’t explain it, but I could sense that I was being protected,” he says. “And still today, when I’m on these journeys, I feel as if someone is looking after me. I sense it and relax. The key is to stay calm.”

As he says this, Rax slowly realises that his anecdote might come off as strange to non-believers, and looks at me timidly. “Now I’ve told you something I’ve never said out loud before,” he says. “I’ve never talked about this.”

The Ice Is Sick

By now, Rax has come to know Greenland and its hunting societies very well. He’s interested in scientific literature about the Arctic, and enthusiastically documents the ongoing changes there with his camera. He says he’s fully aware of the course being played out in the Arctic, but claims his work has no agenda, that he’s simply showing people reality. A student of his work can attest to this: although his photos and books tell certain stories, his personal opinions don’t shine through, neither in images nor text.

“I try to let things float by in front of me, as they are,” he says. “I try to show these people in a respectful way, these grandiose people from a culture of hunters, so that others can see their world and then decide whether they like it or not. I believe they deserve respect because they’re leading a life so different from what the rest of us know. Some outsiders criticise them for hunting bears, but then turn around and eat beef, which comes from animals that are slaughtered too. There’s definitely a bit of inconsistency there.”

Rax says he is very aware of global warming, adding that his friends, the bear hunters, knew about it way ahead of the rest of the world. “They sensed it long before anyone else did,” he says. “Through the years, as I was observing my friend, the hunter, I noticed that he was looking around, sniffing in the air, making observations to others in his group, as if something were amiss. When I asked what was wrong, he uttered the most beautiful thing: ‘The big ice isn’t well, something’s wrong.’”

The hunters patrol the same areas year after year, and they notice the changes, Rax explains. The ice cap that was once 50 centimetres thick is now so thin that they can see through it. “This is something that you can’t see in the photos, as the ice still looks white. You can’t see how thin it has become,” he says.

Rax has started documenting the melting ice of the Arctic for his next project, the growing blue puddles scattered across Greenland. “I’m getting a bunch of people, some big names from all over the world, to write about global warming. I will combine their writing with colour photos of the meltwater,” he says.

He’s really worried about what’s happening in the Arctic, not least for the sake of his children and grandchildren. “We have only one home, one Earth, and we can’t be selfish and damage it and just say “whatever,” to our children. We have to stop just talking about this and do something,” he says.

Lowering his voice, he shyly admits that he’s actually working on a second book. “I’ve just finished writing a children’s story that focuses on this subject, to inspire children to hold respect for the planet.” He recollects how he saw all kinds of features in rocks as a child, and later in icebergs, which he now tries to capture on film. And that’s how his idea for the story came about. “It’s about two snowflakes that get separated and are stuck in ice for thousands of years, one in Iceland, the other in Greenland. But now they’re running out of time to be united before the ice melts.”

This book will not be decorated with Rax’s images. He says he wants it to feature illustrations, adding that he’s no good with a paintbrush. “I’ve always loved looking at paintings and examining painters’ techniques. In some ways, my photos are my versions of paintings. I try to capture similar features in the landscape that I believe many of the landscape painters I look up to did, such as Kjarval [Iceland’s most famous landscape painter].”

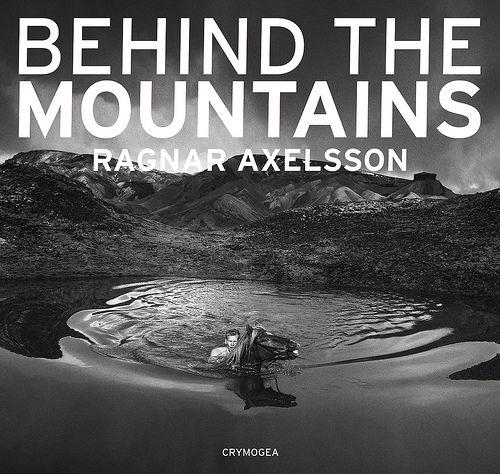

Photo from “Behind The Mountains”

Photo from “Behind The Mountains”

Exciting Times Ahead For Greenland

As an outspoken environmentalist, Rax clearly has an opinion about the Inuits’ ways of hunting polar bears and seals, methods that are widely derided by western societies. He says it’s easy to condemn, but in order to understand the hunters’ circumstances, it’s necessary to stand in their shoes and experience what they do.

“I’ve never participated in the hunting, I never hunt. It’s painful to see a magnificent creature being killed; my heart aches when I witness that. But I understand why it has to happen and try to respect that the Inuit are at least hunting for a living. They eat the meat and use or sell the skins. My hunter friend, who I’ve followed closely for years, once said to me: ‘We are not the defining factor in the existence of the polar bear. It is rather you people, you pollute so much.’ I think he might be on to something there.”

It turns out that this is something that Rax is truly concerned about. He tells me about an article he recently wrote on the pollution of the east coast of Greenland, and relates how a third of the polar bears there are neither male nor female.

“The polar bear is at the top of the food chain, so it must be the pollution in the sea, coming from the rest of the world: plastics, PCBs and what have you. And then the people there eat the bear meat and now there’s been a massive increase in cancer incidents in the area.” Pollution is the biggest threat in the eyes of the Inuit, who feel as if the outside world should first clean up its own backyard before they start criticising the people of Greenland.

Greenland has undergone great changes in the past few decades, most recently attaining self-rule in 2009. Although it’s popular to condemn western societies for imposing their culture on more “intact” cultures such as the Inuits in Greenland, Rax speaks calmly of Greenland’s prospects, smiling again and as optimistic as before.

“I think these are exciting times. The young people there are very bright and well educated and very concerned about their country. They are also very strongly connected to nature; they’re part of it, especially those living in the villages. But I think they want to see changes, new kinds of industry and work. All of Earth’s valuables, metals, gems and oil, can be found in Greenland, so in that regard, it’s one of the richest countries in the world,” he says.

“Corporations from all around the world are queuing up for permits for mining there. I just hope that the people of Greenland can cope with the attention and won’t be fooled. However, pollution inevitably follows mining and when that starts, it will be the first time in history that the people of Greenland pollute their own country themselves. It’s inevitable that the hunters’ societies will change, that there will be fewer hunters around.”

Rax wonders what Greenland is going to look like in 40 or 50 years time. “Will there be a Chinese village in one fjord and an American or Canadian village in the next? If the ice cap melts away, it’s certain that everything will change there,” he says. “It’s a huge country.”

He says his Inuit friends have discussed these matters with him and asked for advice about what to do. “I’ve told them that I can’t interfere, it’s not my place to tell them what they can and can’t do. But I tell them that if they love their country, they should think of it as theirs and not allow it to be treated in a way they don’t like.”

Photo from “Behind The Mountains”

Greenland Vs. Iceland

This topic brings us back home to Iceland, where there’s been a heated debate for decades about whether our nation should harness all of its natural resources, and what would give us more revenue in the long run— selling our green energy to foreign aluminium producers or selling foreign tourists access to Iceland’s pristine landscape.

I ask Rax for his opinion, a man whose life work consists of capturing the magic of intact landscapes and nature in its rawest form. Are we being fooled into sacrificing our nature? He sighs deeply before answering. “There’s no point in holding a grudge against what has already been done, one has to accept and forgive. But in the future, we have to bear in mind what sort of a treasure Iceland is, and…you would never scrawl all over Mona Lisa.” Rax pauses and shakes his head.

“The debate must not be a tug of war between two sides,” he says. “That’s just childish and stupid. People need to try and understand each other’s perspectives. Those who are fond of Iceland the way it is and see value in its beauty have been branded as guerrillas by their opponents, which is just not right. When you’ve travelled all around the world, you come to realise how stunning this country is and how valuable that beauty is. A stupid man observes the world through his window. There are too many people like that, talking down to those who are trying to point out how valuable the landscape is. And it’s as if these people don’t follow what’s going on in the world, never reading about what is happening in other countries, choosing instead to patronise those who do. Some people just don’t seem to be bothered; I often feel that’s a characteristic of Icelanders, not being bothered about anything.”

This is the first sign of negativity Rax displays through our talk, and he quickly brushes it off. He’s also getting restless and fidgety. He reaches for an acoustic guitar that’s tilted against the wall and starts playing a soft Beatles tune, as he tells me he can’t really play the guitar. He just learned a few chords when he was recovering from a hemorrhagic stroke in 2004. “I couldn’t fall asleep at night. I was scared of falling asleep, so I played the guitar until I couldn’t keep my eyes open any longer.”

Although the incident scared him quite a bit, it only slowed Rax down for a short period. After fully recovering, he’s as energetic as ever and remains passionate about his projects. He’s nowhere close to relaxing or retiring, even though he enjoys spending time with his four grandchildren.

“They call me ‘Afi hrekkjusvín,’” (“Granddad, the bully”) he says proudly, as we part ways.

—

Ragnar “Rax” Axelsson’s third book, ‘Behind the Mountains,’ was published on August 23. The photos and the text tell the story of a farmer in South Iceland who, along with other farmers in the area, spend a week every fall gathering their sheep in the southern highlands before winter sets in. The area, Landmannaafréttur, features spectacular, raw landscapes that the farmers have to cross on foot or by horse. Rax has joined the farmers every year since 1988, documenting this annual event which started as chore, but has become so integrated into the farmers’ life that even those who have quit sheep farming continue to embark on the difficult trip every autumn just for the experience.

Rax is a renowned for documenting life in the North. In 2004, he published his first book, ‘Faces of the North,’ portraying people and animals in Iceland and Greenland. His second book, ‘Last Days of the Arctic,’ was named one of the best photography books of 2010 by the Sunday Times in Britain and the German Die Welt. ‘Last Days of the Arctic – Capturing the Faces of the North,’ a documentary about Rax and his photography, was released in 2011 and has aired on television across Europe and America. Rax’s work has appeared in publications such as Life, Newsweek, Stern, GEO, National Geographic, Time and Polka Magazine, and it has been displayed at exhibitions in nearly 30 countries.

Buy subscriptions, t-shirts and more from our shop right here!