January of 2009 was an interesting month for Icelanders. The nation’s economy had just TOTALLY COLLAPSED along with its worldview, trust, confidence and self-image. The government that presided over said TOTAL COLLAPSE was still in power, while the protests that would lead to its ultimate resignation were gaining momentum by the day. It was a time of unrest, and of uncertainty. “WTF JUST HAPPENED?!?” was a popular sentiment, as was “WTF IS HAPPENING?!?” (lest we forget “WTF WILL HAPPEN?!?”).

For our first issue of 2009—‘the annals issue’—we decided to try and capture the atmosphere of the moment by posing two simple, open-ended questions to a lot of people. Here is the introduction from that piece:

What We Had // What We Can Expect: 33 Icelanders Have Their Say

The Grapevine posed a question to dozens of Icelanders, old and new. MPs from every single political party (for some reason, only the Left-Greens cared to respond), ministers, mayors and machinists alike. We asked them to tell us—in their own unique ways, from their own unique perspectives—what summed up the year 2008, and what they expected of the coming one. 2009. We asked them to tell us “What we had,” and to follow with “What we can expect.” Or not. There were no restrictions, our correspondents were free to answer in any way, language and format. From their hearts or from their minds.

Spread over the following pages are the replies we received. Every last one of them. We hope that when read together, in the context of one another, they may give a broad and even enlightening view of how Icelanders as a nation perceived the events of the last twelve months, and how they envision the next twelve turning out. Each and every one speaks for itself, and each one tells a story. Enjoy.

We contacted something like a hundred people for that feature, and thirty-three of them got back to us. Now, three years later, reading over what they had to say is quite revealing, and fun (try it for yourself! Download issue 1, 2009 from www.grapevine.is)!

The combined sentiment paints a portrait of a nation at a crossroads, one that is in the throes of reassessing its values; confused, fearful and hopeful for the future in equal measures. It was a time of great disappointment and uncertainty for sure, but also a time of optimism and hope—one where the local population seemed to be actively involving itself with how its society was being run, where people voiced their concerns and ideas in writing and on the street, participated in think-tanks and generally seemed to be trying their best to not let history repeat itself.

So where are we now?

Frankly, we have no idea. So we thought we’d turn to those thirty-tree again and see what they thought? We sent them their old contributions along with the following question:

“What, if anything, has changed since January 2009, when we published your thoughts on ‘What we had // What we can expect’? And what can we expect now?”

Of course, not everyone got back to us. People are busy. Thirty-three percent of them did, however, and some of those replies are pretty powerful stuff.

Again we hope that when read together, in the context of one another, they offer a broad and even enlightening view of how Icelanders as a nation perceive our three post-kreppa years, and how they envision our future. If nothing else, it makes for a fun, thoughtful read (one that’s sure to be even more fun in three years). Enjoy.

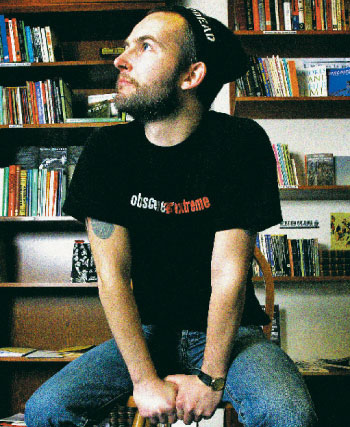

Dr. Gunni, Musician, Journalist

In 2009, many were clinging to the hope of some kind of utopian “New Iceland” to emerge. I was one of them. I read everything I could about current affairs and had opinions and stuff. The old shit that led to the collapse was obviously dead wrong and no way were we going to repeat the mistakes again.

In 2009, many were clinging to the hope of some kind of utopian “New Iceland” to emerge. I was one of them. I read everything I could about current affairs and had opinions and stuff. The old shit that led to the collapse was obviously dead wrong and no way were we going to repeat the mistakes again.

I guess we were being blue eyed fools. Now very few have this hope of “New Iceland” anymore, and certainly not me. The general feel is like nobody at all will even be held responsible for the collapse of 2008, and that the old masters are about to return and not even in a different guise.

I’m so fed up with current affairs and politics that I rarely bother to watch Silfur Egils anymore. Instead of being bothered by the lot, I have turned inwards and just focus on my micro-environment. I like it cosy. I like buying nice stuff and eating nice stuff and having the annual opportunity to leave the country to buy and eat nice stuff on foreign soil. Iceland starts to look quite alright after you have been somewhere else for awhile. Hurray for (old) Iceland!

Bergur Ebbi Benediktsson, Comedian, Writer

Even though people experienced the financial collapse as a sudden event, it was rather a culmination of a series of bad events that had taken place the previous years. In that view, I think that hopes for a quick and sudden recovery were bound not to come true. The society has needed to undergo a thorough scrutiny in all fields, and yes, a lot of things have changed. The traditional political party system was ridiculed during the last local government election, ex-bank managers have been escorted to custody and as of lately the hedonist-proletarian culture (hnakki culture) seems to be collapsing. The pessimists say that things will quickly go back to normal but they are wrong. Things have permanently changed in our young society, it has matured and it now has the chance to pass its adolescent years.

Even though people experienced the financial collapse as a sudden event, it was rather a culmination of a series of bad events that had taken place the previous years. In that view, I think that hopes for a quick and sudden recovery were bound not to come true. The society has needed to undergo a thorough scrutiny in all fields, and yes, a lot of things have changed. The traditional political party system was ridiculed during the last local government election, ex-bank managers have been escorted to custody and as of lately the hedonist-proletarian culture (hnakki culture) seems to be collapsing. The pessimists say that things will quickly go back to normal but they are wrong. Things have permanently changed in our young society, it has matured and it now has the chance to pass its adolescent years.

Hannes H. Gissurarson, Political Science Professor, University of Iceland

Iceland has slowly been recovering from the fall of the Icelandic banks in the autumn of 2008. What has changed is that we now see more clearly that the fall of the banks was a result of external factors working on a vulnerable domestic situation. The difference is that the mistakes or miscalculations of the Icelandic banks have been brought to light whereas the shocking recklessness of many foreign banks, and other financial institutions, is being systematically hidden or obscured by massive public subsidies, by central banks in their countries simply pumping money into them.

Iceland has slowly been recovering from the fall of the Icelandic banks in the autumn of 2008. What has changed is that we now see more clearly that the fall of the banks was a result of external factors working on a vulnerable domestic situation. The difference is that the mistakes or miscalculations of the Icelandic banks have been brought to light whereas the shocking recklessness of many foreign banks, and other financial institutions, is being systematically hidden or obscured by massive public subsidies, by central banks in their countries simply pumping money into them.

The unwillingness of the international community to help Iceland in her hour of desperate need may therefore have been a blessing in disguise. As a result, the banks fell, so we are not overburdened by public debt, like Greece and Ireland, and possibly some other European countries. Instead of subsidising and continuing our mistakes, we corrected them, at least to some extent.

We also see much more clearly now that the history of Iceland since 1991 can be divided into three periods, first of stability, then of drift and lastly of vengeance. The Davíð Oddsson governments of 1991–2004 promoted fiscal and monetary stability, paying the public debt, liberalising the economy, privatising badly run companies, strengthening the pension funds, and creating a feasible way of utilising our fish stocks. The Geir Haarde governments of 2006–2009 just drifted, without sail or anchor. The ministers in the Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir governments since 2009 seem to be bent on just one issue, vengeance against their old political enemies who won most of the battles of the past and all of the arguments. This was shown by their 2009 assault on the independence of the Central Bank, just in order to get rid of Davíð Oddsson, then governor, and the only person of authority who had issued warnings against the vulnerability of the banks in a possible crisis. This was also shown by their extraordinary attempt to impeach Geir H. Haarde, who, inept and weak as he may have been, is as far from being a criminal as any person can be; and who incidentally included in his government since 2007 Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir who was responsible for some of the worst mistakes that government made in finance (such as underfunded government mortgage loans which contributed to the Icelandic credit bubble).

In their thirst for vengeance, the present government ministers have gravely neglected Icelandic interests, as could be clearly seen from their soft position in the Icesave-dispute with the British and the Dutch governments. Those two governments had taken it upon themselves to pay out deposits in the Icelandic branches of the Icelandic Landsbanki, with full interest. The deposits were insured under EEA regulations by the Icelandic Insurance Fund for depositors and investors, an independent agency. When it became apparent that the Fund was not able to cover the outlays of the British and the Dutch governments, they demanded that the Icelandic government paid them what they had themselves voluntarily contributed, on their own initiative, to the balance sheet in the trade between two private groups, the depositors on the one hand and the failed Icelandic bank on the other hand. At the same time, the British government refused to acknowledge, let alone compensate, for the enormous damage it did when it brought down two Icelandic banks in England and for some time put the Icelandic Central Bank and the Icelandic Ministry of Finance on a list of terrorist organisations, alongside the Al Qaida and the Afghan Talibans, briefly stopping in the process almost all communication from Iceland, transfers and trade with the external world.

It was the Icelandic population, led by President Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson and former Prime Minister Davíð Oddsson, who said it loud and clear in two national referenda: We are not going to pay for the recklessness of either Icelandic bankers or of wealthy foreigners in pursuit of high interest rates. We bear no responsibility for these privately created obligations. We should not be worried, either, about international institutions trying to rally to the British and Dutch cause. Every day, the French or the Germans or the Italians break some EU regulation and are being reprimanded for it, without any consequences. Moreover, the Icesave-dispute will probably eventually disappear, as it seems that the failed Landsbanki has enough assets to cover liabilities such as deposits. It is also interesting that probably the assets of the three failed main Icelandic banks will be able to cover about 50% of their total liabilities, which is a much higher ratio than you see with failed banks in North America and Western Europe. This suggests that there is something more to the story than that the Icelandic bankers were only knaves and fools (probably they were no worse and no better than bankers elsewhere).

Iceland’s recovery has been slow, and it has taken place despite the present left-wing government, not because it. The government has tried to dismantle two very efficient systems which were put in place in the 1990s: the tax regime, with relatively low, easily collectible and efficient taxes, and the system of managing the fisheries with individual transferable quotas. There is little awareness within the present government that wealth has to be created, not only redistributed. Iceland, with its good location, accessibility, skilled population and ample natural resources, still has many opportunities to become one of the most affluent countries in the world. Alas, at the moment it is ruled by petty, vengeful characters who put obstacles in the nation’s way instead of removing them.

Hope Knútsson, Psychiatric Occupational Therapist, President of Siðmennt, the Icelandic Ethical Humanist Association

I think we haven’t gotten the whole story yet about what went wrong with Icelandic society although we have some more parts of it than we had two years ago. Until we do, I am reluctant to draw too many specific conclusions other than that I don’t trust most politicians, economists, or any bankers. I am still not too optimistic about the ability of any leaders here to solve the complex, long-running problems this nation faces. Solutions to the massive screw-ups created by the governing parties over the past two decades require that people be very well organised, disciplined, have excellent communication skills, and work in an open and transparent manner.

I think we haven’t gotten the whole story yet about what went wrong with Icelandic society although we have some more parts of it than we had two years ago. Until we do, I am reluctant to draw too many specific conclusions other than that I don’t trust most politicians, economists, or any bankers. I am still not too optimistic about the ability of any leaders here to solve the complex, long-running problems this nation faces. Solutions to the massive screw-ups created by the governing parties over the past two decades require that people be very well organised, disciplined, have excellent communication skills, and work in an open and transparent manner.

Unfortunately none of these skills are very common in Icelanders.

Siggi Pönk, Musician, Activist, Nurse

After the optimism of the ‘pots and pans’ uprising, which was my first experience of massive unity, the public now shares a general state of disappointment. This is a democratic disappointment, as nothing has changed, except that the outlines of the power pyramid that dominates our lives have become clearer while at the same time appearing more unchangeable. I could optimistically quote the British philosopher Simon Critchley, who maintains that all philosophy and possibility of change has its roots in disappointment. But I myself am disappointed and tired and at the moment concerned with saving my own life from the surrealistic distortion of reality that capitalistic representative democracy, peppered with nationalism, offers and too few seem to see anything wrong with. Goodbye.

After the optimism of the ‘pots and pans’ uprising, which was my first experience of massive unity, the public now shares a general state of disappointment. This is a democratic disappointment, as nothing has changed, except that the outlines of the power pyramid that dominates our lives have become clearer while at the same time appearing more unchangeable. I could optimistically quote the British philosopher Simon Critchley, who maintains that all philosophy and possibility of change has its roots in disappointment. But I myself am disappointed and tired and at the moment concerned with saving my own life from the surrealistic distortion of reality that capitalistic representative democracy, peppered with nationalism, offers and too few seem to see anything wrong with. Goodbye.

Björn Þorsteinsson,

Philosopher

Everything and nothing has changed. EVERYTHING, because in January 2009, Iceland was in turmoil, but we were already being told that this particular country was only ‘the canary in the coal mine’, and that the rest of the world would follow. Which is just what happened, or, rather, is happening: unbelievable. But true. And we don’t know how it will end, apparently nobody knows, least of all ‘our’ so-called political leaders. NOTHING, because the system’s still there, unchanging, apparently unchangeable—and for the ruling classes, it’s business as usual, reckless voluptuousness based on the mirthless toil of the 99%.

Everything and nothing has changed. EVERYTHING, because in January 2009, Iceland was in turmoil, but we were already being told that this particular country was only ‘the canary in the coal mine’, and that the rest of the world would follow. Which is just what happened, or, rather, is happening: unbelievable. But true. And we don’t know how it will end, apparently nobody knows, least of all ‘our’ so-called political leaders. NOTHING, because the system’s still there, unchanging, apparently unchangeable—and for the ruling classes, it’s business as usual, reckless voluptuousness based on the mirthless toil of the 99%.

What can we expect? Still more unrest, more police brutality, more states of exception, more rule-bending to serve the ruling few—and, hopefully, a growing, unstoppable counterforce against the powers that be, unsettling them, breaking up their ranks, reclaiming power, putting the demos back in democracy. On a global scale. Here, there and everywhere, from the first world to the third and vice versa.

Real democracy. For its time has come. The means are here, we know them, we have used them to great effect (think: Arab Spring)—and for the rulers, time is getting short: you better watch out…

Katrín Jakobsdóttir, Minister of Education, Science and Culture

The thoughts I am now reflecting on appeared in this publication shortly after The Collapse (capitalised, nowadays) and are indicative of that—I foresaw a difficult 2009, but was hopeful for a shift in values and a changed society. Three years later I can say: The last three years have been difficult. We have not come as far as I had hoped, but we have made some headway. The SIC Report is in my opinion an important testimony of the fact that we investigated the collapse, and will hopefully result in us not repeating the same mistakes that lead us down this path.

The thoughts I am now reflecting on appeared in this publication shortly after The Collapse (capitalised, nowadays) and are indicative of that—I foresaw a difficult 2009, but was hopeful for a shift in values and a changed society. Three years later I can say: The last three years have been difficult. We have not come as far as I had hoped, but we have made some headway. The SIC Report is in my opinion an important testimony of the fact that we investigated the collapse, and will hopefully result in us not repeating the same mistakes that lead us down this path.

I know various changes have been made in Icelandic governance and administration and am optimistic that those will bear positive results. I also believe our society is quickly headed out of the recession, equality has increased and we can see that our infrastructure—for instance our schools and our cultural institutions—stands firm.

I am not as convinced that our values have changed—perhaps they have to some extent, but not at all in as radical a way as I envisioned in the last days of 2008. Perhaps it takes more than three years for an entire society to reconcile with as hard a blow as The Collapse proved to be.

Aftaka.org, Anarchist Orchestra

From agriculture to nanotechnology, through the Enlightenment, Industrial Revolution and an alleged End of History, the history of mankind has been a history of repression of the individual. Under the yoke of church and state, economical systems and property rights, technological development, society and morality, individuals’ dreams and desires for freedom have been crushed in the name of the so-called interests of the masses.

But the history of human kind is also a history of the rebellion of individuals who have struggled their way from under the rules of their oppressors and attacked them, alone or in union with others, expanded their deepest longings far beyond the framework of the permissible, blamelessly followed their own sense of justice albeit at odds with the bourgeois justice, refused to confess to the idea of a better society after a revolution, and instead created and lived in accordance with their own ideas, here and now.

During the last three years, considerable changes may well have occurred in many people’s minds. But essentially, these years have operated as a well oiled machine in the metronomic rhythm of history. If anything, the repression seems to have proliferated. Wilderness decreases and Caesar Augustus’ registration of the entire world is still taking place, increasingly accurate and effective as history repeats itself more frequently.

Therefore, precisely, individuals should learn from their rebellious predecessors: how they have consistently nosed out exits, not hesitated in creating these exits if they don’t already exist; and not in the least if, and then how and why, they have failed. All of this, not in order to follow their exact footsteps, but to be inspired, to diligently choose weapons and create one’s own path while walking.

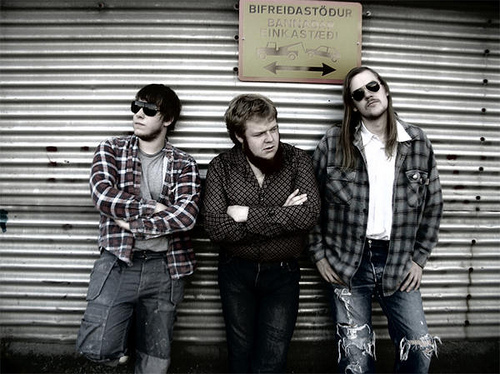

Haukur V. Alfreðsson musician, journalist

The people in charge sure have turned completely gray in colour. And so many people are just so angry. It’s like an addiction. The angry people are now able to get their fix wherever and whenever they want.

The people in charge sure have turned completely gray in colour. And so many people are just so angry. It’s like an addiction. The angry people are now able to get their fix wherever and whenever they want.

I’ve had it with anger and bad attitude. The kreppa is dead to me. Now I’m just waiting for the new James Bond film. Let’s all just do that.

Kristín Björk Kristjánsdóttir, Musician

As satisfying as it could be to blast out something that I feel has drastically changed between now and then, it really is a bit obscure to me. Except that lately I feel like there’s a new sense of raw and wild, something pure and untamed splattering about in visual art especially but also in music. Less focus on shiny polished, more on guts, intuition and energy.

As satisfying as it could be to blast out something that I feel has drastically changed between now and then, it really is a bit obscure to me. Except that lately I feel like there’s a new sense of raw and wild, something pure and untamed splattering about in visual art especially but also in music. Less focus on shiny polished, more on guts, intuition and energy.

Actually I spend a lot of time abroad, but this is my experience from the lay of the art and music land when I’m in town.

Speaking of which, the best piece of new music I saw played live last year is by composer Hlynur Aðils Vilmarsson, performed live at the Dark Music Days Festival in Listasafn Íslands. Not that I ever heard anything but wonder coming from this secretive, unassuming genius boy.

The most memorable concert I saw last year was Ben Frost, solo at the Berghain club in Berlin. It’s a great inspiration to see a solo artist channel his music in a live situation with as much confidence—a perfect example of how engaging electronic music can be live with some guts and sparkle.

One of the most fun musical discoveries of the year for me was a girl from Ghana called Oy, who I saw play during Iceland Airwaves. Her set totally blew my mind! I’m sure it was her that conjured the lightning that struck Iðnó while she was playing. Her new record, ‘First Box Then Walk’ is a very exciting, witty piece of work. I could go on forever about all kinds of crazy amazing music that moved me last year, but you’d need a special issue for that.

Þorvaldur Gylfason, Economics Professor, University of Iceland

Oh, lots of things have changed.

Oh, lots of things have changed.

For starters, the IMF has now left the stage, having helped Iceland to weather the crisis with money and, more importantly, as always, advice.

Like it or not, the technical know-how necessary to navigate the treacherous waters engulfing Iceland as the banks collapsed in 2008 did not exist in the country’s civil service, and so foreign assistance was absolutely essential. Had the authorities—to avoid losing face—asked the Nordic countries for help rather than the Fund, the Nordics would almost surely have directed Iceland to the Fund, the world’s chief source of expertise in dealing with deep banking crises. So, the IMF was the only game in town, with significant input from the Nordics. Not even the political opposition in parliament, let alone civic society, proposed serious alternatives to the Fund-supported rescue operation.

And now, three years after the crash, the economy is beginning to grow again, partly because the exchange rate of the króna appears at long last to be roughly correct, which is good for exports as well as for domestic firms competing with imports. It follows that unemployment is remarkably low. Even so, inflation remains too high and too many households find it difficult to make ends meet. Eurostat reports that 13 percent of Icelandic households find it very difficult to make ends meet compared with 2 percent to 4 percent in Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden. In our part of Europe, only Spain (14 percent), Portugal (20 percent), Greece (24 percent), and Latvia (24 percent) have relatively more households in such dire straits. Where it counts, Iceland has clearly parted company with the Nordics.

So, Iceland still has miles to go.

Besides, it remains to be seen how the IceSave twist will play out in court. It appears quite possible that Iceland will be required to pay a significantly higher amount of money than was stipulated in the agreement between the Icelandic, British, and Dutch governments that was defeated in the second IceSave referendum of 2011. It also remains to be seen how the cases expected be brought by the Special Prosecutor against those suspected of having robbed the banks from within and others will fare in court.

As I see it, the cleanup after the crash must rest on two pillars to achieve its purpose: first, the economic reform and reconstruction now underway, and, second, court cases against those suspected of having broken the law. The nine-volume, 2.300-page report of the Special Investigation Committee of the parliament paved the way. The Financial Supervisory Authority has referred to the Special Prosecutor almost 80 cases of suspected violations of the law in connection with the crash. The total number of cases is expected to exceed 100 when all is said and done. Attempts to unseat the post-crash director of the FSA have thus far failed.

How long will it take for Iceland to regain economic and social parity with the Nordics? This is impossible to know. For one thing, no one knows how long the rather stringent capital controls will remain in force, controls that were originally intended to last only two to three years and should, therefore, have been out of the way by now. Also, no one knows whether the political class will revert to its nasty old habits now that the IMF is no longer calling the shots from short distance. Further, no one knows how the cases against those who pushed Iceland off the cliff will fare in court.

A failure by the authorities to produce convictions—to make the culprits behind the crash face justice—may have a demoralising effect on the population to the point of triggering significant exodus from the country, to Norway and other places. This must not happen. The country cannot afford it. Economics and law, efficiency and fairness, must go hand in hand.

—–

Buy subscriptions, t-shirts and more from our shop right here!