In post-collapse Iceland, mortgages are hard to come by, and a growing number of people are turning to the rental market. Yet, with such increased demand, finding apartments to rent for would-be tenants is only getting more difficult.

So where are we supposed to live?

“When we advertise an apartment for rent, it’s gone two or three days later,” Brandur Gunnarsson, a real estate agent at Stakfell agency tells me. “We continue getting inquiries about it for the following two weeks, though. A rental usually gets at least fifty to sixty enquires.”

Another real estate agent, this one working for Eignatorg, Björgvin Guðjónsson, says that in his opinion the rental market is very underdeveloped. “When you find a flat to rent, it’s typically because it’s for sale or the owner is not using it for a short period of time,” he says. “So you regularly have to move, and it’s difficult to find an apartment that you could rent for ten years.”

In fact 56% of Icelanders say that there are either few or very few rental housing options that would suit their family’s needs, according to a Capacent poll conducted for the Housing Financing Fund (Íbúðalánasjóður) in October 2011.

A TEMPORARY OPTION

It has long been the government’s policy to encourage home ownership and the large majority of Icelanders own their homes today. As a result, the rental market is historically small and has been seen as a temporary option. While this wasn’t such a problem before the financial crisis of 2008, when loans were given to just about anybody, it has become increasingly evident that the housing needs of a fair chunk of people are not being met.

There appears to be a problem that needs solving.

The Housing Financing Fund (Íbúðalánasjóður, HFF) was founded by the government to provide individuals with loans for the purchase, construction and renovation of residential housing in Iceland, or as its director Sigurður Erlingsson puts it, “it’s a government agency with the task of making sure Icelanders have a place to live.” Sigurður confirms that there is increasingly a demand for rental housing in the greater Reykjavík area.

“Our polls show that crash or no crash, people still want to own their homes,” Sigurður says. “Icelanders are quite individualist, and much like Americans, they pride themselves in owning a home.”

However, it’s not that simple. The post-crash reality is that not everybody can afford to buy a home. “I think the obvious reason is that there is a larger group of people who, due to their finances, are not eligible to borrow money,” he says. “We can see in our polls that there is a direct connection between having a poor state of finances and entering the rental market.”

In fact, 24% of all people applying for a regular mortgage last year said that they were denied, according to the aforementioned Capacent poll. “That was really surprising,” Sigurður says, “and it supports the idea that there are some people who need to rent because they won’t be able to get a loan in the next few years.”

HOMES FOR EVERYBODY!

Prior to the financial collapse, nearly everybody was eligible to borrow money. The game-changing year is 2004, when recently privatised bank entity Kaupþing began offering competitive housing loans. Not only were they competitive with the HFF, but they were also “allowing up to 80% loan financing (as opposed to the 70% limit applicable to HFF at the time),” a July 18, 2011 EFTA decision states.

This led the other two large private banks to offer similar mortgages, which in turn led the HFF to lower interest rates on their mortgages and to lend on a higher loan to value ratio, with the HFF briefly offering up to 90% loan financing.

Meanwhile, the banks were offering up to 100% loan financing and in some cases bank loans far exceeded property value. A particularly glaring example is a certain home in 101 Reykjavík, which was advertised for auction with a debt to Arion Bank (formerly Kaupþing) totalling 516.821.227 million ISK (around 4 million USD)—a property that had been valued at 77 million ISK (around 600,000 USD) in March 2010.

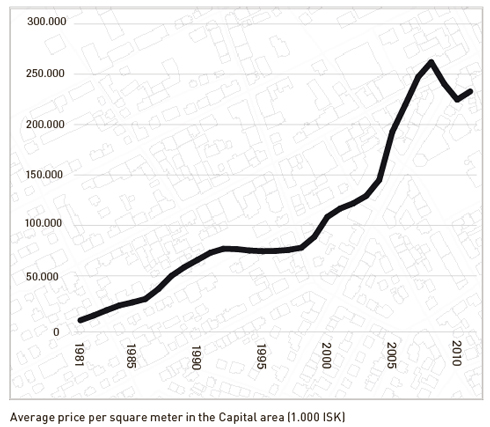

In light of these developments, housing prices skyrocketed—within two years, apartment prices in the capital area had doubled.

PROBLEM?

In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, it turns out that the lending system was problematic for a number of reasons. First, loans pegged to foreign currency—which have since been ruled illegal—became up to two times as expensive due to the króna’s plummet. Second, indexed loans—which make up the bulk of the housing loans—became significantly more expensive due to the crisis-induced inflation.

“Of course inflation has been a problem in Iceland for a long time,” Sigurður explains. “The indexation was meant to encourage owners of money to lend because nobody wants to lend money long-term without being sure that it won’t burn up.”

This worked fine for the last 30 years when salaries typically exceeded inflation, but it became clear that there was a flaw in the system when the trend reversed. “Suddenly the relationship between salaries and inflation didn’t hold true,” Sigurður says. “People’s salaries have been kept constant for three years while cumulative inflation has gone up over 40%. This is why people are so angry.”

In other countries, such as in Poland and Chile, where mortgages have been indexed, salaries were also indexed so that the mortgage payment is always relative to salary. “Iceland is, as far as I can tell, the only country using a system where obligations are indexed but salary is not,” Sigurður says. “My personal view is that the system is flawed.”

“PROPERTY ISN’T GOING ANYWHERE”

While Iceland’s current leftist government has taken some steps to relieve the resulting debt burden facing homeowners—for instance, by passing the Law on Mitigation of Residential Mortgage Payments—many still find themselves in a tight spot. In 2011, the Central Bank of Iceland submitted the following information to the EFTA Surveillance Authority:

– 25% of households have mortgages that are more than 500% of annual income (debt situation);

– Around 12% of households use over 50% of their disposable income to service their mortgages (debt service ability);

– The total debt service of 1/6 of households is in excess of half of their disposable income (debt service ability);

– Around 20% of households have negative net assets and 22% have only a marginally positive net equity position (net assets of households).

Despite all this, housing prices have not plummeted. Bucking a trend seen widely in post-collapse Europe, Iceland’s housing prices are rising.

This is not making it any easier for the average person to enter the housing market.

“I think the rising housing prices can somewhat be explained by the capital controls, which mean that there are limited investment opportunities. If you want something safe, you can buy government bonds or you can buy a house. It’s basically a flight to safety for investors. You hear stories of people taking money out of the bank or from under the mattress and putting it into property, which is not going anywhere,” Sigurður says.

“There’s also a limited supply of new properties. Hardly any homes have been built since 2008, so there is a shortage, which is especially evident with smaller apartments selling for less than 15 million ISK. People—typically young people buying their first home—fight heavily for the smaller apartments. So it’s just supply and demand at play.”

THE GOVERNMENT’S NEW AGENDA

Working on behalf of the Ministry of Welfare (formerly the Minister of Social Affairs and Social Security), a consultative committee charged with looking into ways to meet changed housing needs post-crash, reported in 2011 that the percentage of households in long-term rental homes is lower in Iceland than it in most European and Nordic countries and recommended that government officials work toward strengthen the rental market.

While the previous government encouraged home ownership through interest benefits given to offset the mortgage costs of purchasing residential housing, Sigurður tells me the that the current government plans to re-evaluate this system in the coming years so that it does not discriminate between ownership and non-ownership.

“After the crash people have been saying that it is not desirable to have a system that encourages you to borrow. Obviously you always have to borrow some amount to buy a home, but the current system encourages you to borrow even more because that entails benefits and interest repayments,” Sigurður explains. “The benefits should not pull you one way or the other.”

DEVELOPING A RENTAL MARKET

Due to foreclosures, the HFF—which, as a state institution, cannot go bankrupt—now owns 1750 properties. “Instead of having a fire sale—shaving off thirty percent and putting them on the market—the plan is to slowly put their properties on the market,” Sigurður says.

Of those 1750, Sigurður says 650 are rented out. “If people lose their home, we are obliged to offer that person or the tenants living in the home a twelve month rental contract,” he says. “After that we have no obligation, but we have been renewing contracts for the second or third time.”

In the meantime, the HFF owns 1150 that currently not on the market. Thus far the properties that HFF owns have otherwise not been available for rent, but by summer, Sigurður says they will for the first time be on the rental market. “We have properties that we could sell or we could rent and we will try to do either one,” he says. “Of course, especially in areas where there is a shortage of rental housing, like here in Reykjavík, we will try to increase the supply of rental housing.”

The banks too own a number of apartments, which are also collecting dust—or so they think. While there are no official numbers, a number of people have taken up squatting since the financial crash.

In one case, a couple moved into an empty apartment on Laugavegur after the banks foreclosed on its previous owners. While it sat empty, a radiator exploded leaving water to sit in the empty apartment for an unknown period of time. The damage is evident as I peak inside and there is a musty smell, but the couple say they live comfortably and rent-free. They tell me that a bank representative once showed up to find them there, but ultimately did nothing.

In another case, certain tenants have found themselves living for free when the apartment they inhabit get repossessed—it seems the collapsed banks creditors are not all that interested in reaping from their investments.

“The apartment we were renting was auctioned off from under the owners,” a 29-year-old student tells me, “they just arrived one day and told us that it had been auctioned off to the bank. Then nothing happened for almost a year. We just stopped paying rent, and the new owners never showed up to claim it or attempt to charge us rent. I’ve heard of lots of other examples of this happening, I am sure there are people living for free right now all over Reykjavík.”

DEMYSTIFYING THE MARKET

Sigurður says the rental market is still very much a mystery. “After we accumulated so many properties I realized that the market was like a black box,” he says. “I had no way of finding out how many people were renting in the market. Nobody could give me a precise answer.”

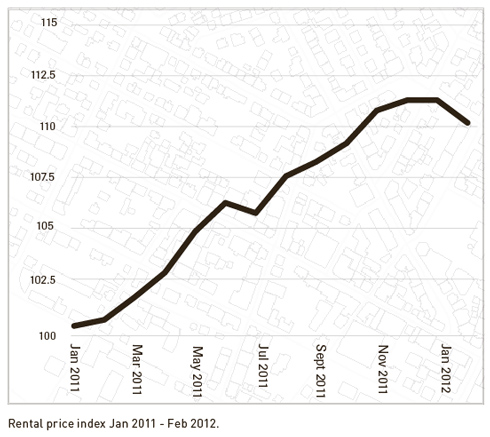

The first step HFF is taking to develop the market is to make it more transparent. “What we have been doing, for example, in collaboration with The National Registry (Þjóðskrá), is figuring out what the market price for rent is in different areas,” he says. “We are also encouraging that all rental agreements be registered so that we can absorb pricing data and people will have a better idea of what it will cost them to live and rental companies that want to invest in property somewhere can accurately estimate how much they can rent it out for.”

With data about the cost of renting by size and location last year published time by the National Registry in collaboration with the HFF, for the first time last February, it is possible to start analysing the rental market and whether it is makes sense to rent or to buy.

RENT IS NOT CHEAP

Naturally, the rental market varies depending on whether we’re talking about Reykjavík or Ísafjörður. And it probably comes as no surprise that it’s most expensive to rent in downtown Reykjavík, postal code 101.

A two-room, 63 square metre, apartment in 101 Reykjavík rented for an average 109.863 ISK/month in 2011. To afford rent, somebody working full-time (171 hours/month) at minimum wage (182.000 ISK/month in 2011) would need to work 103 hours, which is 60% of the work month.

There is slight variation in the average price of an apartment in the greater Reykjavík area, with a pocket of lesser expensive apartments being found in Breiðholt, which has a large concentration of social housing. Still, somebody working at minimum wage would need to work at least 87 hours in a month to afford rent there.

The least expensive apartments are located in the remote Westfjords. An average two-room, 63 square metre, apartment in Ísafjörður, which is considered the capital of this region, rented for 57.477 ISK/month in 2011. To afford renting this apartment, somebody working for minimum wage would need to work 54 hours per month, which is 32% of the work month.

LESS EXPENSIVE TO BUY

The price-to-rent ratio—which compares the price of a home to what it would rent for over a twelve-month period—is widely used in the Unites States to determine whether it makes more sense to rent or to buy in the current housing market. It is generally believed in the States that if the ratio is above 20 that it is a better idea to rent while if it is below 20, it is a better idea to buy.

If the same threshold applies in Iceland, preliminary price-rent calculations by the HFF indicate that in all Reykjavík postal codes, renting is more expensive relative to buying—with the ratio ranging from 14 in downtown Reykjavík (postal code 101) to 10,65 in Breiðholt (postal codes 109 and 111).

This of course is a rough measure, but as a rough measure it suggests that rent is high for the current housing market conditions. So it seems that Icelanders’ almost philosophical aversion to renting is partly based in the stubborn pride depicted in Halldór Laxnes’ ‘Independent People,’ and partly in the fact that at the moment buying still seems to make more sense.

Unfortunately it’s just no longer an option for everybody.

—–

Have a look at our interactive map displaying the average rental price for a 63 square metre 2-bedroom apartment in Iceland and our previous article Renting In The Free World.

See a larger version of this map.

Buy subscriptions, t-shirts and more from our shop right here!