Overrun by Viking ambition, Reykjavík Energy built headquarters fit for Darth Vader, expanded ambitiously, dabbled in tiger prawn farming and flax seed production, went into the fibre optics business, invested in a new geothermal plant, speculated in places like Djibouti, and finally managed to run itself so completely into the ground that foreign investors will no longer offer the company loans.

In hopes of rescuing its multi-utility service company from the depths of abyss, the city of Reykjavík stepped in this March with a 12 billion ISK (105 million USD) loan, which is nearly its entire reserve fund set aside for the company, but still only a fraction of the company’s massive foreign debt of 200 billion ISK (1.7 billion USD).

With thousands of captive lifetime subscribers and a means of producing energy at very little cost, the company had all the makings of a cash cow. So what happened to Reykjavík Energy, an entity that less than a decade ago was a perfectly viable, municipally owned company providing the city with basic utilities: cold water, hot water and electricity?

From the top floor of Reykjavík Energy headquarters, an expansive view of Mount Hengill can be observed on the eastern horizon. The mountain range forms part of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge as it cuts through Iceland and divides the country between the North American and Eurasian continental plates. It is one of the most geologically active areas in the world.

Two thick white clouds of steam can be seen rising up from the mountain where Reykjavík Energy operates the Nesjavellir and Hellisheiði geothermal power plants. Together the plants provide hot water and electricity to more than half of Iceland’s population of 318.452.

Over the last half century, Iceland has successfully established a name for itself as a world-renowned leader in the field of geothermal energy, using it to heat 90% of the country’s buildings and nearly all 136 swimming pools in the country. As Iceland’s President Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson said at a geothermal conference last year, “We were very fortunate that while most of the world forgot about the geothermal sector, we had visionaries in Iceland. Not just scientists and technical experts, but also local councillors in towns and cities who saw the opportunities in this area.”

The President is well known today for having travelled the world during Iceland’s boom years giving laudatory speeches about the nation’s valiant bankers who led the country to economic prosperity, to the extent that some have called it cheerleading. However, since the crash he has abandoned the bankers, and now travels the world singing songs of praise for Iceland’s geothermal “visionaries,” who, instead of the bankers, helped “transform a country of farmers and fishermen into one of the most prosperous welfare economies in the world.”

The story goes, as he told it in Xiamen, China last year, “In my youth, over 80% of Iceland’s energy needs came from fossil fuel, imported coal and oil. We were a poor nation, primarily of farmers and fishermen, classified by the UNDP as a developing country right down to the 1970s. Now, despite the effects of the present financial crisis, we are among the most prosperous nations in the world, largely due to the transformation which made our electricity production and space heating based 100% on clean energy.”

He emphasises the last point that Iceland’s geothermal energy business has served to offset the effects of the economic crisis: “Yes, indeed,” he said in Abu Dhabi, Bali, and Shanghai last year, and again in New York this year, “geothermal energy has helped Iceland to survive the recent banking shock […].”

While the story that the President tells about Iceland’s transformation to geothermal energy is indeed marvellous, and it is true that the cost of heating and electricity is nowhere in Europe cheaper, one would have to be wearing rose-tinted glasses to see Reykjavík’s geothermal energy business as a saviour in the crisis. Upon closer inspection it appears that the country’s largest multi-utility geothermal energy company, which claims to operate “the largest and most sophisticated district heating system in the world,” has only driven the nation into deeper water.

A FINANCIAL BASKETCASE IS UNVEILED

When The Best Party came to power in Reykjavík after the May 2010 elections, the comedian-turned-Mayor Jón Gnarr said he was surprised to learn that Reykjavík Energy was in such a horrible financial state. “I had always had the impression that it was the wealth in the city,” he said of the company that is 94% owned by the city Reykjavík and exploits what is arguably Iceland’s greatest resource.

Yet despite the abundance of resources and a steady demand for its services, Reykjavík Energy managed to rack up a 233 billion ISK debt (2 billion USD or 1.4 billion Euros), which is nearly four times the city’s annual budget of 60 billion ISK. What’s more, 200 billion ISK (1.7 billion USD or 1.2 billion Euros) of this debt is in the form of foreign currency loans, which fluctuate at the whim of the króna.

“For months I found myself in daily meetings directly or indirectly related to Reykjavík Energy,” Jón Gnarr told me, admitting that it grew very tiresome. It was around that time, on September 25, 2010 at 11:43 pm, that he wrote the Facebook status update that would come back to haunt him in the form of political ammunition six months later [our translation]: “Reykjavík Energy is bankrupt. The city is in bad shape and its revenue has decreased. What should be done? Cut backs? Price increases? Streamlining? Where and how much? Meetings, meetings, meetings…”

Aiming to clean up the mess, Jón Gnarr’s team brought in Haraldur Flosi Tryggvason as Chairman of the Board and made him a full-time executive director with the gargantuan task of getting the company back on track. The initial ‘rescue operations’ included orchestrating a mass layoff of 65 employees in October 2010 and raising the price of heating and electricity by 27% between November 2010 and January of this year, to little fanfare from citizens and employees alike.

Though the decision to hire Haraldur Flosi was initially criticised because he had been the head attorney at Lýsing, a company that guaranteed the now-deemed illegal foreign currency loans to individuals, he is also one of the few Chairmen in the history of Reykjavík Energy to have a background in business. “We have made an effort to hire people based on professional training and experience rather than political affiliation,” Jón Gnarr told me.

In February, Haraldur Flosi had been noticeably cautious when he explained to me how the company managed to accumulate such colossal debt. “If the crash had not happened, it wouldn’t have been nearly as bad,” he said. “When the financial crisis hit, Reykjavík Energy was in a huge expansion period, so it was quite exposed to the crash, and because loans were mostly financed in foreign currency, the company’s debt about doubled overnight.”

The company chose foreign loans with a favourable interest rate of 1–2% over domestic loans with an interest rate of 10–15%. Had the company taken domestic loans at the higher interest rate, the debt would not have doubled in the crash, but it would nonetheless have been equally large today, Reykjavík Energy PR Manager Eiríkur Hjálmarsson would later tell me.

While this suggests the company’s massive debt cannot be wholly explained by the crash, Haraldur Flosi was not interested in pointing any fingers. He admitted that the company was perhaps over-optimistic in its investments, but yet his explanations were mostly framed by the economic crash.

“The biggest problem today is getting financing,” he said. “Foreigners have become sceptical of the situation here in Iceland. It’s more difficult to get access to money and it’s more expensive,” he told me, adding diplomatically, “but I think it’s the same everywhere. Many companies abroad are also struggling to adjust to this new reality. This is in a nutshell what happened.”

Less than one month later, this problem became more evident. Unable to secure loans from Deutsche Bank, Barclays, Citibank, Council of Europe Development Bank, European Investment Bank and Nordic Investment Bank, Reykjavík Energy announced on March 29 that it would be dipping 12 billion ISK deep into the city’s reserve fund, which had been set aside for a situation like this.

At the same time, the company announced that it would cease paying the city its annual 800 plus million ISK in dividends, it would continue raising the price of hot water and electricity, it would lay off another 90 employees, and it would begin selling off all assets unrelated to its core business. These assets include everything from a fibre optics business to The Pearl, a Reykjavík monument. Russian investors with ties to Ásgeir Þór Davíðsson from the sleazy Kópavogur strip club Goldfinger have already made an offer on Perlan, expressing an interest in turning the omnipresent monument into a flashy casino.

THE BEST PARTY TAKES THE RAP

Despite the fact the Reykjavík Energy had been heavily in debt for years, little had been said about it. “The state of the company should have been pretty clear for some time now,” Jón Gnarr told me, “but for some reason, while Icesave featured heavily in the public discourse, nobody talked about the state of Reykjavík Energy though the company debt is four to five times the Icesave debt.”

As soon as news of the emergency loan from the city broke, however, a blame game ensued. Fingers were pointed in all directions, but despite the fact that The Best Party is the only political party in Reykjavík that did not have a hand in running the company during the decade that it accumulated its monstrous debt, the fingers pointed were generally in the direction of Jón Gnarr and the new Reykjavík Energy directors.

It started on March 27 with an article on news website Vísir.is blaming Jón Gnarr and the new directors for making it difficult for the company to get its loans refinanced. As seems customary in the Icelandic media, Vísir based the entire story on an anonymous source: “According to our sources from the financial world, getting loans refinanced has not been going well, due to, among other reasons, comments that have been made by the directors and Jón Gnarr.”

Specifically, the article said, according to their sources, investors had received a translation of one of Jón Gnarr’s Facebook statuses: “Reykjavík Energy is bankrupt.” The status, which has since been deleted (and is quoted above in its entirety), was posted in September 2010, six months prior to the Vísir story.

This continued to be a point of contention for others, like Independence Party City Councillor and former Mayor of Reykjavík Hanna Birna Kristjánsdóttir, who publicly criticised Jón Gnarr for his comments about the company being bankrupt. She also disagreed with the idea of phrasing the city’s 12 billion ISK loan as a city bailout, which implied bankruptcy. This is despite Reykjavík Energy CEO Bjarni Bjarnarson claiming that the company would not have been able to continue paying employee salaries without the loan.

Then, on March 30, Haraldur Flosi’s predecessor as Chairman, Guðlaugur Gylfi Sverrisson, wrote a letter to the media both to make it known that when he was Chairman—between 2008 and 2010—the company had always been able to secure loans, and to accuse the new Board of fumbling a loan that was essentially a sure grab.

“In January 2010 the CFO of Reykjavík and the CFO of Reykjavík Energy met with the Nordic Investment Bank (NIB). They [NIB] expressed great desire to lend Reykjavík Energy 12–14 billion,” he wrote. “…In June 2010 when I left as Chairman, there were no doubts that NIB would loan the company the previously mentioned amount given that the company met stipulations [to raise prices].”

He concluded his letter with the implicating questions: “What changed after June 2010? Could it be that comments made by the directors and owner about the financial state of Reykjavík Energy have negatively influenced its ability to get financing?”

Sigurður Jóhannesson, a Senior Researcher at the University of Iceland Institute of Economic Studies, put it this way on a University of Iceland radio show: “I probably wouldn’t say that my company were bankrupt if I was trying to get loans, but I think that investors must look first and foremost at things like cash flow and annual financial statements. One can also read reports by rating agencies, and there is very little there mentioned about Jón Gnarr.”

Anna Skúladóttir, who was Reykjavík Energy’s CFO from May 2006 until 2011, met NIB in January 2010 and she confirms in conversation that “the bank expressed interest,” but it was by no means a done deal. “In 2010, foreign loans weren’t just closed to Reykjavík Energy,” she said. “Iceland as a whole was still on ice.”

Ultimately though, the bigger questions remain: What happened to Reykjavík Energy before Jón Gnarr and the Best Party enter the story in June 2010? And, could it be that something happened before 2010, which would explain the company’s financial state?

WHEN MONEY GREW ON TREES

Reykjavík Energy was founded through the merger of the institutions Reykjavík Electricity (Rafmagnsveita Reykjavíkur) and Reykjavík District Heating (Hitaveita Reykjavíkur) in 1999, and Reykjavík Water Works (Vatnsveita Reykjavíkur) in 2000. The company thus began on solid ground, with a long history of well-managed services to captive subscribers, respectively dating back to 1921, 1930 and 1909.

Historian (and active Left Green member) Stefán Pálsson, who worked as a curator of the Reykjavík Energy Museum for ten years before he was let go in the mass layoff last October, explained that the institutions were so lucrative that they had to find ways of spending money so that they wouldn’t show too much profit.

“They would, for example, hire hundreds of school children every summer to plant trees, make roads, and work on environmental projects,” Stefán said. “They would rationalise that we are harnessing geothermal energy from this area so we owe it to society to plant loads and loads of trees. And we give school children jobs, which makes their parents happy, which is good for society, and things like that.”

In fact, the institutions that preceded Reykjavík Energy were so lucrative that politicians could milk them to fund pet projects and other vanities. For instance, it was under Davíð Oddsson’s legacy as Mayor of Reykjavík that District Heating financed the construction of The Pearl, a well-known monument in Reykjavík, which opened to the public in 1991. “It was never supposed to turn a profit,” Stefán said. “The big tanks carry hot water, but then there is the building on top, the restaurant, and the sightseeing deck. And actually it was supposed to be even more extravagant with palm trees and tropical birds and plants.”

Nonetheless, the institutions were loaded with money and owed very little when these endeavours were carried out. It was not until after the institutions were turned into a private partnership company (sf.) in 2001 that the debt begins to amass.

A SLEEPING GIANT STIRS

If there is one person who has been most closely associated with Reykjavík Energy over the years, it is Progressive Party politician Alfreð Þorsteinsson. Alfreð’s involvement began in 1994 when he was appointed Chairman of a municipal body charged with overseeing the three institutions. It was under his leadership that the institutions were merged into Reykjavík Energy in 1999, and from then until 2006 he served as Chairman of the Board of the new company.

Alfreð, along with Guðmundur Þóroddsson, the former head of Water Works who was hired as CEO, were keen on stressing that Reykjavík Energy was now a company, Stefán explained. “We the staff were told that we were not to refer to it as an institution.”

This shift in mentality was also mirrored by a shift in the legal framework governing the company. A specific law, no. 2001/139, which was passed in 2001, gave Reykjavík Energy the right to take small loans and make payments for the purposes of running the company without the consent of its owners (the municipalities, Reykjavík, Akranes and Borgarbyggð). It also gave the company the right to operate subsidiaries and to invest in other companies. In essence, it enabled Reykjavík Energy to be run like a private company, while retaining a political management.

“The idea was that this new company was a sleeping giant that had been ineffective in the past. It had almost endless credit because it owed next to nothing, and around early 2000 that was not really something to brag about in Icelandic society; it was seen as an unused opportunity. You had this potential of taking loans to grow,” Stefán told me.

“The same argument was made to regular people who had paid off their mortgage; they were told that this made no sense, that it was downright silly. So people refinanced their homes, took a new loan to be paid over twenty years time instead of five, and this freed cash to play in the stock market, or to buy a summer house or a new jeep. I would say that Reykjavik Energy’s troubles stem from a large-scale version of the same thing.”

In the case of Reykjavík Energy, unleashing the power of capital meant buying tens of small district heating companies in the south and west of Iceland, expanding their service from five to over twenty municipalities. “You got the impression that somewhere in Reykjavík Energy there was someone with a map, putting down flags, you know with a Napoleonic dream of taking over,” Stefán jokingly remarked.

Additionally, Reykjavík Energy began investing in other companies, and by 2003, it had shares in over twenty companies, including Feyging ehf, a flax seed operation of which it was the largest shareholder. That project was abandoned in 2007 with a loss of 340 million ISK. An attempt to farm tiger prawns was also declared a failure in 2007, after seven years of work and 114 million ISK down the drain.

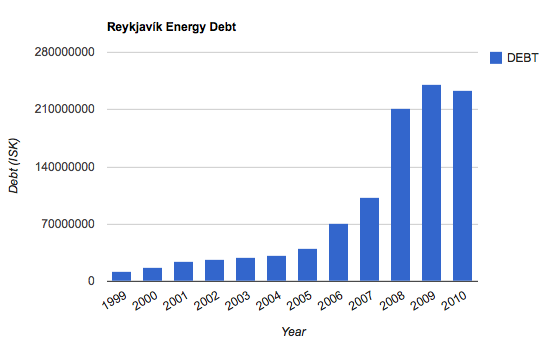

Alfreð, the former Chairman of the Board, is adamant that the investments were not too many or made too quickly. “When I left in 2006,” he told me, “the company’s debt was less than 70 billion ISK. The state of the company was very strong. The loans taken were all long term, to be paid off in 20–30 years.” In any case, that debt is still nearly seven times the debt that Reykjavík Energy inherited through the merger of the institutions in 1999.

BIG INDUSTRY FULL STEAM AHEAD

That being said, the bulk of Reykjavík Energy’s debt can be attributed to the construction of the Hellisheiði plant, which former Reykjavík Energy CFO Anna Skúladóttir said is “the largest investment in the company’s history.”

The decision to build the plant, she said, was made in the beginning of the 21st century when it became evident that the Reykjavík area would need more hot water as the Nesjavellir plant was expected to become fully utilised. At the same time, the decision was made to harness 300 megawatts of electricity to be sold to heavy industry, as it was considered more efficient to build and run a plant that produces both hot water and electricity.

In 2006, the company reached an agreement to sell electricity to aluminium smelting company Century Aluminum Norðurál, but when the crash hit in 2008, Reykjavík Energy had yet to secure financing for phase five of the plant build-up, including the 90 MW that were supposed to go to Norðurál in 2010.

By that time, however, it had already purchased five turbines at about 5 billion ISK a pop. “Turbines must be ordered at least three years in advance,” Anna explained. “It’s like ordering an airplane.”

Two of the five will come online this year, but an agreement was reached to postpone delivery of three of the turbines until a decision has been made to continue further plant production. Of the three outstanding turbines, Reykjavík Energy didn’t have a definite energy source lined up for the third one. What’s more, there were originally seven, not five, turbines ordered, but Independence Party politician Kjartan Magnússon said he was able to back out of two of them when he took over as Chairman of the Board in 2008.

When Moody’s reviewed the company for a possible downgrade in July 2008, it noted: “The company’s financial profile has continued to weaken during the course of the year, mainly due to the company’s exposure to unhedged foreign currency debt, the company’s primary source of funding. Conversely, 80% of its revenues today are in Icelandic krona derived from its operations as Reykjavik’s primary multi-utility.”

Despite the risks involved, however, it has essentially been government policy to attract heavy industry to the country. In the span of a decade, Iceland’s aluminium production went from 4% of the country’s GDP in 2000 to 14% in 2010—surpassing the country’s fish exports and making Iceland one of the largest aluminium producers in the world. “The ‘heavy industry agenda’ was a big part of the bubble in Iceland,” Minister for the Environment Svandís Svavarsdóttir said.

“The Left Greens always put a question mark next to heavy industry, but it was really the mainstream view. When we suggested that it was possible to do something else, people said, well ‘do you want to knit socks and pick mountain herbs?’ The Left Greens were considered a very foolish party for not wanting to proceed with heavy industry.”

Following the city’s bailout, though, it has been increasingly debated whether a municipally owned company should take the risks associated with making these kinds of heavy industry deals given that the city and its taxpayers are accountable. Not only is Reykjavík Energy financially incapable of continuing with phase six of the Hellisheiði plant for the time being, but they have also for the first time turned their back on the company’s heavy industry policy.

“We think that Reykjavík Energy should fulfil its role as a service company that provides people with electricity, hot and cold water, and sewage disposal,” Jón Gnarr explained. “We don’t think it should participate in heavy industry or other risky investments.”

BLOWING THE LID OFF 2007

Though it was undoubtedly unfortunate that Reykjavík Energy was in the middle of raising capital for the Hellisheiði plant when the crash hit, the company nonetheless made some very questionable decisions in 2007 at the peak of Iceland’s financial boom. For instance, the Board decided to buy shares in Hitaveita Suðurnesja for 13.4 billion ISK despite the fact that the company didn’t have any spare funds. The shares were paid for in entirety with a five year loan, which is due to come back to bite the company in 2013.

Perhaps, though, the spirit of the times is best captured in Reykjavík Energy’s decision to boost its geothermal operations overseas through a subsidiary company called Reykjavík Energy Invest (REI). At the same time as the banks had reached nearly ten times the nation’s GDP by expanding offshore, Reykjavík Energy also aspired to a world domination that made Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson proud. “I allege that if we continue like this,” he told a TV2 reporter in October 2007, “the Icelandic energy ‘outvasion’ can be an even bigger operation than the banks.”

The event that the President was praising is now commonly referred to as the REI scandal, in which Reykjavík Energy briefly merged its subsidiary company Reykjavík Energy Invest with Geysir Green Energy, a private company owned by, amongst others, FL Group and Glitnir bank, which were highly implicated in Iceland’s banking collapse.

According to an article that appeared in Fréttablaðið on October 4, 2007, REI’s project list included the building and buying of about 700 MW of energy in the United States, Philippines, Greece, Indonesia, Germany and Ethiopia. Their goal was to produce three to four thousand megawatts before year-end 2009, at which time they planned to go public. “These are very ambitious goals that will lead to the biggest geothermal energy company in the world,” FL Group Chairman Hannes Smárason told Fréttablaðið.

Though Reykjavík Energy Chairman of the Board at the time Haukur Leósson sincerely believed that the merger was in the best interest of the company, noting that they had negotiated 10 billion ISK for the use of Reykjavík Energy’s brand name alone, it is widely believed that there was foul play involved. When the former CEO of Glitnir and Chairman of REI Bjarni Ármannsson admitted in 2009 that the merger between REI and GGE had been a mistake, Independence Party politician Gísli Marteinn Baldursson wrote on his blog, “Hopefully he now realises that there were other things than our deliberation that have done more damage to Iceland and one would wish that more had shown care.”

Ultimately, the grand plans never materialised. After the company introduced the idea to the Board, news of the meeting went to the media and people were especially outraged to hear that key staff at Reykjavík Energy were being given special stock options. “There was so much anger,” Svandís Svavarsdóttir recalled. “I did a lot of interviews in the span of two to three days. I’ve never felt anything like it. It was like everything was burning in society. There was a lot of heat.”

The controversy led the Independence Party and Progressive Party majority municipal government to fall apart, and a new majority between the Social Democrats, Progressives, Left Greens and Liberal Party formed with Dagur B. Eggertsson becoming Mayor of Reykjavík.

While the so-called ‘100 day majority’ reigned, a steering committee headed by Svandís with representatives from every political party was set up to look into the events and to determine whether any lessons could be learned. The more they learned, the more it became clear to them that the merger should be stopped. They felt that Reykjavík Energy had developed too far from its owners and on its own initiative.

“In many ways, the REI story is a prototype of the financial crisis. Politicians decided to allow private individuals into public entities and let them behave as if they owned what belonged to the public,” Svandís told me.

“We saw that on a large and small scale in society. We saw it in the privatisation of the phone company, the banks, in the privatisation plan of the right-leaning government, which ruled for far too long, for eighteen years, but in Reykjavík this was basically the same thing that happened.”

At the same time as the REI deal was being discussed, an attempt was also made to privatise Reykjavík Energy. Part of such a proposal, which was put forth by CEO Guðmundur Þóroddsson and Vice President Hjörleifur B. Kvaran on August 28, 2007 rationalised that “[i]t is time to unleash the energy of free enterprise so that Iceland’s expertise and knowledge can be used to the fullest extent in the geothermal energy company outvasion.”

On September 3, 2007, the Board actually approved sending the proposal to the owners of the company for approval, e.g. the Mayor of Reykjavík, the City Manager of Akranes and of Borganes. However, the idea fell by the wayside when the frenzy erupted over Reykjavík Energy Invest. “Since then it hasn’t been brought up again, and I doubt it will be,” Svandís said. “Well I hope not.”

Reykjavík Energy Invest still exists today though its ambition is far from the grandiose dreams of its founders. Independence Party City Councillor Kjartan Magnússon, who became Chairman of Reykjavík Energy in January 2008, a few months after the REI scandal exploded, explained: “We decided after I became chairman to fulfil our commitments in projects abroad, in Djibouti for instance, but to stop the financing of such projects thereafter, and instead focus on selling knowledge and expertise.”

Said Anna Skúladóttir: “Unfortunately, looking back I think that everyone ran around crazy in 2007, it didn’t matter whether it was the municipality, State, companies, individuals—everyone was blinded. Hopefully we’ve learned something from this and can look forward.”

It might be noted that in 2009, Reykjavík Energy purchased a 7.1 million ISK Mercedez Benz ML 350 for Anna’s personal use. Anna went on to return the car in 2010 after Icelandic tabloid DV ran an indignant story about it.

A ROSY STORY INDEED

Though the crash alone is a convenient excuse as Reykjavík Energy’s debt doubled in 2008 due to fall of the króna and financing became more difficult, it could also be said that Reykjavík Energy was as much a victim of the financial crisis as Iceland’s banks were a victim of the United States mortgage crisis.

Truth be told, Reykjavík Energy managed in less than a decade to run a perfectly viable company into the ground, despite having the ingredients of a cash cow. As President Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson tells Icelanders, foreign leaders and journalists alike, geothermal know-how in Iceland is first class, and people come from all over the world to see it firsthand.

“We have great competitive advantages,” Ólafur said at a geothermal conference last year. “One is that Iceland is the only place in the world where you can, in a single day, witness all the aspects of geothermal utilisation. You can witness three geothermal power plants, a greenhouse town in a farming area, a world famous international spa, a medical clinic, as many swimming pools as you want to and visit fishing companies that use geothermal energy for drying their products.”

He continued: “…When we bring people here, they are inspired, they have a vision. They leave Iceland full of hope, inspired by the possibilities. That is very important, because political decision-making and even business decision-making need more than mere calculations. They also need a vision and inspiration—hope. That is what we can give.”

With all the geothermal know-how in the world, however, Iceland’s largest multi-utility geothermal energy company was inspired by a vision that took hold of Iceland during the financial bubble, which grew rapidly for a decade, peaked in 2007 and then burst in 2008.

Despite the dark outlook presented by rating agencies for Reykjavík Energy, Jón Gnarr is optimistic. “The state of Reykjavík Energy is still difficult, and it’s very sensitive to exchange rates,” he said, “but I believe that the plan that we have initiated is very good, and I am confident that the state of Reykjavík Energy will improve.”

Meanwhile, our president isn’t deterred. “The reason why I have emphasised the geothermal experience of Iceland as well as the technological know-how is that I believe this the most significant contribution we can make to the battle against climate change, which seriously is the most fundamental threat that the world faces,” he told us over the phone when we asked him to explain his geothermal rhetoric.

“Even if one company in Iceland does badly it doesn’t mean that we should think to take this away from other countries, and quite frankly there is such a strong demand from the world to have access to Icelandic cooperation in this area that our problem is to meet the requests and they come from poor countries in the developing world to rich countries in Europe and the Western world.”

—

HEADQUARTERS

Price tag: 4.271,7 BILLION ISK

As the company struggles to stay afloat, its headquarters, which were built in 2002 under the chairmanship of Alfreð Þorsteinsson, stand as a symbol of what many believe to have been the excessive and ill-founded investments of the municipally owned company.

“A service company for the people of Reykjavík has no business building a house like that,” Independence Party representative Kjartan Magnússon disapprovingly told me. “The people of Reykjavík felt it was part of a power game. When you come into this house, it’s a sign of power.”

Similarly, former employee and historian Stefán Pálsson called it a monstrosity. “You would expect it to be Darth Vader’s Headquarters. It is my advice to politicians connected with Reykjavík Energy never to allow themselves to be interviewed outside the building.”

On a visit to the infamous headquarters, Chief Press Officer Eiríkur Hjálmarsson, a company veteran since 2006 and the lone survivor in the PR department after the October layoffs, showed a photographer around the building. He took us to top floor to see the view over Mount Hengill, where the company operates the two power plants at Nesjavellir and Hellisheiði.

Since our visit, that floor has been put on the rental market. The advertisement is telling: “Fantastic 745m² office space on the sixth and top floor in Reykjavík Energy is available for rent immediately. The building is fully equipped with the best of the best and has access to a big rooftop balcony with a vast unhindered view over the city…”

It continues: “In the house is a staffed reception, World Class (luxurious fitness centre), with optional access to lecture rooms, a library, computer room, and more […]Special housing for those with demands. Blue prints and more information can be solicited from our sales men, trod.is.”

The ad doesn’t mention it, but the building also houses impressive art, including a 35 metre tall granite fountain by artist Svava Björnsdóttir, which travels through all five floors of the building, and a Foucault Pendulum, which takes 26 hours to knock down all the pins before they pop up again.

However, former Chairman of the Board Alfreð Þorsteinsson doesn’t think it’s overly extravagant. “The main fault of the house is that it is considered beautiful and chic,” he said. “If it had been built as a one or two story house nobody would have said anything. Should we have built an ugly house?” Furthermore, he said the top-class kitchen, which has been heavily criticised is “not unlike other kitchens in Reykjavík.”

—

THE REI SCANDAL

The course of events

January 25, 2007

Former Reykjavík Energy CEO Guðmundur Þóroddsson proposed to the Board that Reykjavík Energy create a subsidiary company called Reykjavík Energy Invest (REI), which would oversee all of Reykjavík Energy’s stakes in ventures abroad, including Enex, Enex-Kína, Galantaterm and Iceland American Energy. The Board approved.

March 7

The Board additionally agreed that Reykjavík Energy would put two billion ISK into REI towards future projects. A report that was commissioned at the January 25 Board meeting and then delivered at the March 7 Board meeting noted: “There is great interest amongst Icelandic investors in environmentally friendly energy, for instance, Geysir Green Energy hf, Atorka hf and Enex hf. The first two named have already requested a partnership with Reykjavík Energy in the outvasion.”

June 11

Reykjavík Energy Invest was formally founded. Appointed to the Board were Björn Ársæll Pétursson, Haukur Leósson, and Björn Ingi Hrafnsson. Reykjavík Energy CEO Guðmundur Þórodsson would replace Björn Ársæll Pétursson as CEO in September.

September 11

Former CEO of Glitnir Bjarni Ármannsson was appointed Chairman of REI and bought stock worth 500 million ISK.

September 20

The Directors of REI met with banksters Hannes Smárason from GGE and Jón Ásgeir Jóhannesson from FL Group to discuss merging the companies.

September 22

Chairman of REI Bjarni Ármansson met with Chairman of GGE Hannes Smárason to flesh out the details of the merger.

September 23

Chairman of REI Bjarni Ármansson and Chairman of Reykjavík Energy Haukur Leósson met with Mayor of Reykjavík Vilhjálmur Þ. Vilhjálmsson at his home to brief him on the merger. Vilhjálmur did not inform his colleagues in the Independence Party about the merger until October 2, which greatly upset them, and led to a rift in the Independence Party.

October 3

Reykjavík Energy held a Board meeting and an owners meeting to introduce the merger. Invitations to the meeting were sent out the previous evening, which is extremely short notice. Nonetheless, the Board approved the merger, save for Svandís Svavarsdóttir from the Left Green party, who did not vote.

News of the meeting and specifically news that key staff were being given special stock options blew up in the media. The majority government between the Independence and Progressive parties collapsed. A new majority, dubbed ‘The 100 Day Majority’ took over. A steering committee headed by Svandís Svavarsdóttir began investigating the events that led up to the merger and proposed to City Council that the merger be thwarted.

—

‘OUTVASION’

Yes, it’s a made up English word

The term ‘outvasion’ is a direct translation of the Icelandic word ‘útrás,’ which is often used to describe Icelander’s expansion overseas. The ‘útrásavíkingar’ or ‘outvasion Vikings’ refers to the businessmen who set out to conquer the world with a Viking-like ambition that ultimately brought about Iceland’s downfall in 2008.

—

A correction has been made to the online version of this article. Iceland is one of the largest aluminium producers in the world rather than the largest aluminium producer in the world as it was stated in the print version.

Buy subscriptions, t-shirts and more from our shop right here!