The tenth annual festival, which opened on September 26 and continues through to October 6, is comprised of 75 features as well as a number of Icelandic shorts and special events. In fulfilment of RIFF’s mission of bringing this culture to Iceland, as festival Chair Hrönn Marinósdóttir put it to the Grapevine last year, Icelandic audiences will have a chance to see films fresh off appearances at Cannes, Venice, Toronto, and other high-profile festivals; and directors, from the world-renowned to the up-and-coming, will be appearing alongside their work. As a survey of the world-cinema buffet RIFF offers up, we sent out questionnaires to filmmakers who’ll be in town to present their work; a selection of their responses is below, and more responses can be found at grapevine.is.

‘Coldwater,’ a competition title and the feature directorial debut of California-based Vincent Grashaw, concerns a troubled teenager who is sent off to a wilderness boot-camp reform facility.

How did this film come into existence, and why?

I started writing the script when I was fairly young, about 18 years old. I knew I wanted to make movies and had known a kid who was abducted in the middle of the night and sent to a camp for juvenile delinquents. I didn’t know how bad in reality these issues were until I began researching. I brought on my writing partner after several failed attempts at trying to get the movie made. So it wasn’t like I researched for 13 years and made the product which is the movie… it just evolved over the years, as I matured as a filmmaker. It wouldn’t be the same movie if I had made it back then, so I’m grateful for the years of struggling to do it the right way.

What discussions did you have about the visual style of the film? When you’re making a film like this (fact-based, violent stakes), is there a conventional look that you’re conscious of?

My cinematographer and I spoke a lot about how we felt the film should look. I did feel that because the beautiful landscape in the wilderness environment is a heavy contrast to the violence and experiences of the characters in the film, that it would definitely stand out visually. I wanted it to feel like a theatrical motion picture—not a stripped-down, down and dirty independent film. I feel like technically the film holds up with any movie in a cineplex. Regardless of the dark subject matter, it’s a fictional story and I wanted it to be a thrilling moviegoing experience which stands on its own.

“Expedition to the End of the World” documents the voyage of a schooner with a crew of artists and scientists that sailed through the melting ice of northern Greenland. Danish director Daniel Dencik was aboard:

How did this film come into existence, and why?

A ship was going to sail to an unexplored land; a producer heard about it and asked me if I wanted to film it.

What did you learn in making the film?

That it is megalomaniac of us to think that we can destroy Earth.

What’s the most interesting response (rewarding, critical, thought-provoking or bizarre) you’ve thus far received from someone who’s seen the film?

In a theatre in Switzerland, a person fainted and an ambulance had to come. Apparently it was a case of Stendhal Syndrome: something is so beautiful that it paralyses you and eventually leads you into a state of psychosis.

Is there any element of the film that you’re especially interested in sharing with an Icelandic audience?

There is one shot of Iceland in the film, disguised as a shot on Greenland. Try to figure out which one…

How is ‘Expedition to the End of the World’ different from ‘Encounters at the End of the World,’ aside from the fact that they take place at literally opposite ends of the world?

I think Herzog is great. Maybe his film is more like a Western than mine, and my film is more like an opera than his.

In “Vanishing Point,” documentary filmmakers Stephen Smith and Julia Szucs explore the lives of Inuit communities in Canada and Greenland, particularly looking at how they are coping with social and environmental change.

What’s the most interesting response (rewarding, critical, thought-provoking or bizarre) you’ve thus far received from someone who’s seen the film?

Interestingly, we have found that even vegetarians and those who do not directly relate to hunting culture have been supportive of the film. We wondered whether we might get a negative response from those opposed to hunting, but it seems that instead there is a response of respectful understanding of the necessity for Northern peoples to a live a lifestyle that includes hunting and an animal flesh diet. Perhaps this follows on the heels of a growing awareness of the problems of industrialised agriculture. So we’re finding what is for us a surprising interest from audiences to understand what it means, culturally, to increase one’s self-reliance and security when it comes to food harvesting.

Is there any element of the film that you’re especially interested in sharing with an Icelandic audience?

We are confident that Icelanders, who also live close to nature and have a strong sense of independence and self-reliance, will relate to the marine hunting culture that is the focus of the film. For those living close to the sea, there is a dependence on an intact and sustainable approach to managing and harvesting from the marine ecosystem. We hope that Icelanders will enjoy immersing themselves in the lives of those who—partially due to geographic isolation—must look to their immediate environment for food security and cultural integrity.

In ‘Naked Opera,’ director Angela Christlieb follows Marc Rollinger, a terminally ill Luxembourgian civil servant who travels around Europe attending productions of Mozart’s “Don Giovanni,” staying in high-end hotels and treating himself to rent boys.

What did you learn in making the film?

In a technical sense, I learned how to shoot a documentary like a fiction film, but without a script and without knowing what will happen the next day. This put me in some really delicate situations because Marc is not an actor, he is a real personality, and he tried to control the movie. So I learned to improvise in very critical moments—as long as there was enough champagne and boys, things were OK. In a human sense, I learned about how people behave when they suffer from a critical illness.

What’s the most interesting response (rewarding, critical, thought-provoking or bizarre) you’ve thus far received from someone who’s seen the film?

In Tel Aviv someone in the audience said: I can’t believe a woman made this film.

“The Moo Man” is a profile of Steve Hook, an independent English dairy farmer, who has a very close emotional bond with the cows that produce his raw milk.

Andy Heathcote and Heike Bachelier are co-directors:

What did you learn in making the film?

We learned a lot about cows, what nice creatures they are, full of individual character. We learned even more about raw milk, but also about how impossible it is for farmers who are interested in animal welfare and in producing good quality food to survive in a world dominated by supermarkets. So ultimately we learned a lot about the mechanisms that destroy small family farms worldwide.

What’s the most interesting response (rewarding, critical, thought-provoking or bizarre) you’ve thus far received from someone who’s seen the film?

The most challenging response so far was from the ex-deputy agricultural minister in the UK who came to one of our screenings. He claimed we portray a very idyllic way of farming and if all farms were like this in the UK we couldn’t feed the country. To hear this argument from someone who should be at the forefront of protecting small farms was shocking. Plus, it is not true anyway.

“Spaghetti Story,” a competition title, concerns a quartet of aimless young people and a Chinese prostitute in modern-day Rome.

Ciro De Caro is the writer and director:

There have been films about aimless young adults trying to discover what they want out of life since at least ‘I Vitelloni,’ though the specifics vary greatly from generation to generation. Do you think of your film more in terms of what it has in common with other stories in this tradition, or in terms of what makes it new?

I really tried to learn something from the masters of the classic Italian comedy, a kind of sad comedy, permeated by this particular Italian “skill” of laughing about problems and taking life with irony. What I tried to do was to put our real life, our everyday little tragedies, in an ironic movie, because that’s the Italian way (I think) of telling stories. I’m far from putting myself at the same level of the big masters of Italian cinema, but I think that, in this particular moment, as a young Italian director, I have to treasure this legacy we have. Because we Italians have no money to make a Hollywood movie right now, and even if we could find such money, I think the result would be something “wannabe Americano.” We should remember that we have this particular ability to make great things from simple stories in a simple way. That’s why the title of my movie is ‘Spaghetti Story’: it’s made like a spaghetti dish, which is simple, genuine, economical and Italian.

The Italian-born, English-based producer Uberto Pasolini’s newest effort as a director is ‘Still Life,’ starring Eddie Marsan as a self-contained government employee whose job is to locate the next of kin of local residents who have died at home alone. He winds up growing close to Joanne Froggat as one such relative.

What did you learn in making

the film?

Before writing the screenplay I spent a year researching various aspects of the story, and I became increasingly aware of the growing isolation that touches so many people in our western cities where the breakdown of the family unit and of old neighbourhoods condemn vast numbers, both old and young, to lives without true human contact. So I have certainly become more sensitive to the need of involving oneself in the lives of others and letting others come into your own life—things that appear obvious but are often hard to make real.

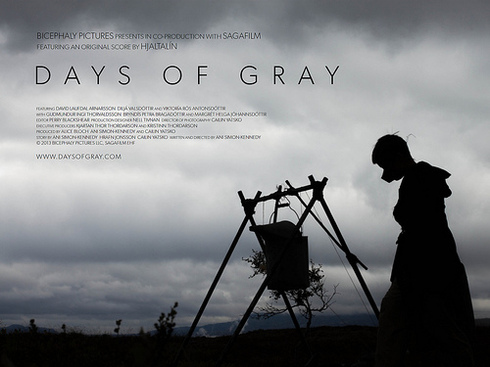

‘Days of Gray’ is a post-apocalyptic fable set in a world without language. The dialogue-free film shot in Iceland features a score by the Icelandic band Hjaltalín. It is the first feature by the NYC-based director Ani Simon-Kennedy

How did this film come into existence, and why?

Cailin Yatsko, my cinematographer, and Hrafn Jónsson, my writing partner, went to see Hjaltalín perform in Prague when we were all living there while in film school. Their music completely took my breath away and we immediately began to build a story around their music. After sharing the concept with the band, they decided to create an original score for the film. So the music gave life to the movie which gave life to the music.

Is there any element of the film that you’re especially interested in sharing with an Icelandic audience?

I can’t wait to be able to present the film at RIFF since it’s been a little over a year since we shot in Iceland with an all-Icelandic cast. I had never been to Iceland when I first started writing ‘Days of Gray,’ but from everything I had researched and from what Hrafn had told me, it seemed like the perfect setting. ‘Days of Gray’ really couldn’t have been filmed anywhere else but in Iceland, and being able to work with and befriend so many Icelandic people, I really believe that between their solidarity and resourcefulness, it’s the one place on Earth where you could survive the apocalypse.

Buy subscriptions, t-shirts and more from our shop right here!