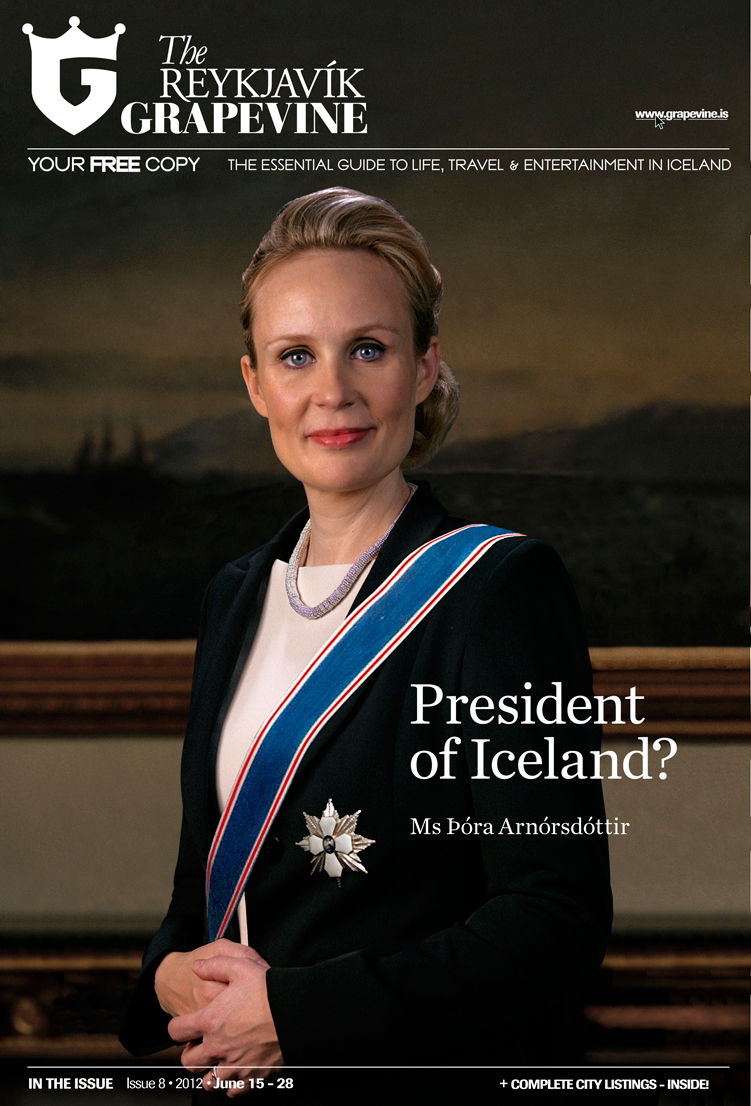

Incumbent President Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson is Iceland’s fifth elected president. If re-elected on June 30, he will become the longest-sitting president in the history of the Republic. For the first time since he entered office in 1996, Ólafur faces real competition, with opposition candidate Þóra Arnórsdóttir polling right behind him. We met Ólafur at Bessastaðir, the official presidential residence where he has lived for the last sixteen years, to find out why he is running.

When you first ran for president in 1996, what drove you? What did you aspire to do? How did you decide that you were cut out for the job?

I wouldn’t put it like that. The process leading up to my candidacy in 1996 was characterised by people from all over the country sending me letters, calling me, urging me to run for the presidency. This is unlike in many other countries where candidates decide themselves that they want to run for the presidency, and then they build up a machine and a big electoral system. It is an inspiring experience to go through this democratic process in Iceland. It shows that what in the classical philosophical literature is called the ‘will of the people,’ is a reality.

I have always been motivated by public service. So when I decided to run for president I saw it primarily as a way to serve the nation and to contribute to its advance. I also thought that at a time when globalisation was in its early stages, I could help to build bridges between Iceland and other countries and also help to convince the young generation of Icelanders that they could have a fascinating life as global citizens while being rooted in Iceland.

PROMOTING ICELAND

You don’t think you went too far? For instance, you’ve been criticised heavily for being too friendly with the ‘útrásavíkingar’ [“Outvasion Vikings”—a term used to denote Icelandic bankers and businessmen who were active in Iceland’s expansion/bubble].

‘Útrásavíkingar’ is a propaganda term that has been used in Iceland. What did it entail? It entailed promoting a large collection of many different companies. Of course there were the banks, but there were also companies that are still going strong, companies that have in fact become the pillars of the Icelandic recovery, companies like Marel, Össur, CCP, Actavis, Icelandair, and many others.

I can also give you the example of LazyTown. You could ask yourself, is Magnús Scheving an útrásavíkingur? He came to me in the second year of my presidency with a play about LazyTown, which the National Theatre had refused to stage because a play about kids eating apples and doing gymnastics was boring. Magnús wanted to take it global. Since then, Dorrit [Moussaieff, first lady] and I have tried to help him, in the United States, Europe, China, Latin America and elsewhere, in the same way as we have helped designers, tourism companies, artists, and musicians.

I believe that it is the responsibility of the president to promote activity that can grow into productive contribution to the country. Of course there is no guarantee that they will all succeed. If the president can help to convince young Icelanders that their country of birth is their best option, I think the president has served the country well.

THE PRESIDENT’S ROLE

Right, so what is the president’s role?

There are many roles. As the highest elected official, the president’s role is to represent the republic. If the political parties in Iceland fail to agree on a government, it is also the president’s responsibility to make sure that the country has a government. The history of the Republic shows us that this can indeed occur.

The president also has the authority to make sure that if a large part of the population wants to exercise its democratic will to decide on major issues, he can refer the matter to a referendum.

In addition, I think the president has increasingly become the spokesman for the nation in the global community, especially through the global media. You could say that this is a role that started somewhat in the time of Vigdís [Finnbogadóttir]. It didn’t exist for the first three presidents because the global media simply didn’t exist. This has increasingly become the role of the president, especially following the financial crisis, due to the Icesave dispute. I then had to enlarge this contribution in a big way because Iceland was being attacked in the global media. There were all kinds of falsehoods floating around, so it was important for me to come forward and defend the country and speak on its behalf.

But is it the president’s role to define the role of the president?

There’s no single forum where the role of the president is defined. First of all, the fundamental basis of the presidency is defined in the constitution. Second, it is the will of the people that defines the role of the president. Many people forget that when they talk about the presidency; they analyse it backwards and forwards without once mentioning the term democracy, but that is the essence of the presidency. No president, whatever his or her wishes, can go against the national will. You could therefore say that the ultimate definer of the role of the president is the people.

The third dimension is the international environment. There is an endless series of events and meetings that relate to that dimension. Within these three dimensions—the constitution, the will of the people, and the international community—there are of course the desires and the views of the president himself.

Speaking of which, you recently said that the role of the president is not only to take walks and to think. What did you mean?

Sometimes one hears views that the president should simply sit here in Bessastaðir, read the books in the library, walk around the beautiful area, and then occasionally come forward like a wise man and utter some wisdom about the nation. I don’t think in the twenty-first century that it is doable for a country to operate a presidency like that.

Some people say that I’m too active, doing too much, that the president shouldn’t be so involved. Then my question is, should the president say no to all these requests from communities, individuals, organisations, and educational institutions? Should I say no to the international media? Should I have said no to The Economist, which asked me to make a keynote speech at the World Ocean Summit? Should I say no to Google? Should I say to this multitude of people, ‘No, sorry, now I’m going to reflect’?

A CHANGED PRESIDENCY

Do you think the presidency has changed during your time? That you’ve changed the presidency?

There have been changes in our society. It has become much more multidimensional. All these non-governmental organisations that are interested in the environment, in welfare issues, in better health, in the fight against drugs, didn’t exist 30 to 40 years ago. They all ask the president to be involved.

There seems to be some resistance to this change.

We live in a free democracy. People are perfectly capable of saying anything that they want about the presidency. It doesn’t necessarily mean that they are right. Many people have said that I have changed the presidency, but I have not done anything that is not within the framework of the Constitution.

They are probably not referring to the fact that you’ve technically changed it, but that you’ve exercised powers that no other president has exercised.

Of course I’ve done that. I’ve exercised Article 26, but what people have to realise is that a presidency in the age of global media, in the age of the internet, has to be, by its very nature, different than the presidency in the 1950s.

THE WILL OF THE PEOPLE

Traditionally, you haven’t had much competition, and the presidency hasn’t been much of a competition. How is running today different than it has been in the past?

I’ve always had the view that the presidency is a democratic responsibility and therefore an election every fourth year should be the normal thing. I’ve never subscribed to the view that once you are elected you have an automatic right to the presidency. So I welcome this election. I think it is a healthy sign and it offers the nation an opportunity to debate the presidency.

You’ve said that part of the reason that you’re running is because of uncertain times, the EU, the government…

As you know, I was urged by over 30.000 Icelanders to continue the presidency for a number of reasons. Many of them have to do with fundamental issues that have now been put on the table, the constitution is being completely revised, nobody knows what kind of constitution we’re going to have in two or three years time; new political parties have been formed; we’re negotiating EU membership; the economic crisis in Europe is still going on—we have never in our history had so many fundamental uncertainties.

Would you trust anybody else to take on these uncertainties?

That’s not my view. People asked me to do it. People have given me their trust for sixteen years and I believe I have a moral obligation to listen to them. It will also give me an opportunity, if I’m reelected, to use the next four years to make two contributions, which I think are very important. One is to try to make sure that the nation stops arguing about so many fundamental, divisive issues, that we try to eliminate these disagreements, reduce the tension in our society. Secondly, to help the nation to establish a solid foundation of progress in Iceland; help people to do new and fascinating things in many different areas.

Do you think you are a divisive figure, at odds with the government?

I don’t think I’m a divisive figure. Every president in Iceland has had to make decisions that have created opposition. Vigdís, for example, has described in her autobiography how opposition to her decision to sign the European Economic Area Agreement was such that people stopped greeting her in the streets. All the other presidents also made decisions that made them unpopular or divisive for a while.

The president can, however, in many ways—through his effort, presence, and voice—try to help the nation to sort out big conflicts. No society can, for a long time, have so many fundamental and critical issues on the table. Just as no society can be healthy if parliament, the institution that sets the laws and rules, enjoys less than 10% trust.

I know many people have a critical opinion of me, but I believe that on the basis of my experience, I can try to help the nation to sort out these conflicts and move the attention from these divisive struggles and issues over to more constructive tasks, like building Iceland up as a forum for new things.

Finally, why should people vote for you? What sets you apart from the other candidates?

I have never ever said why people should vote for me. I didn’t do it in 1996, and I won’t do it now. The nation knows me well—it knows my good sides and my bad sides. When people vote, they should vote on the basis of what they think is best for the nation, not based on what the candidates tell them. Why do I say that? Because I see the presidency primarily and solely as a service to the people.

—

Full name: Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson

Born: May 14, 1943, in Ísafjörður (Age 69)

Education: BA in economics and political science and PhD in political science from the University of Manchester

Occupation: Ólafur is currently serving his fourth term as President of Iceland. He has served as Minister of Finance, as a Member of Parliament for the left-wing People’s Alliance (Alþýðubandalagið). Prior to his roles in public service, he was a lecturer and the University of Iceland’s first Professor of Political Science, as well as the editor of political newspaper jóviljinn. He is currently number 21 on the list of the world’s current longest ruling non-royal national leaders.

Tidbit: Ólafur has a dog named Sámur, named after the loyal canine of Gunnar, a main character in Njál’s Saga.

—

Read interviews with the other candidates:

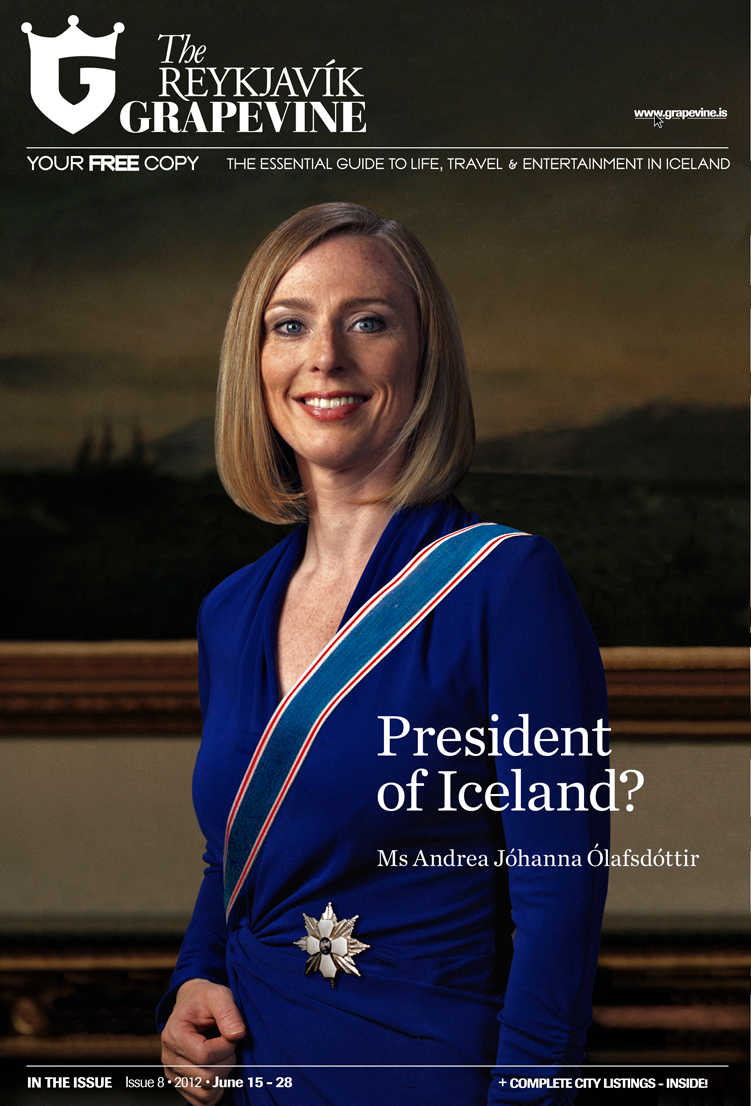

Andrea Ólafsdóttir

Andrea Ólafsdóttir

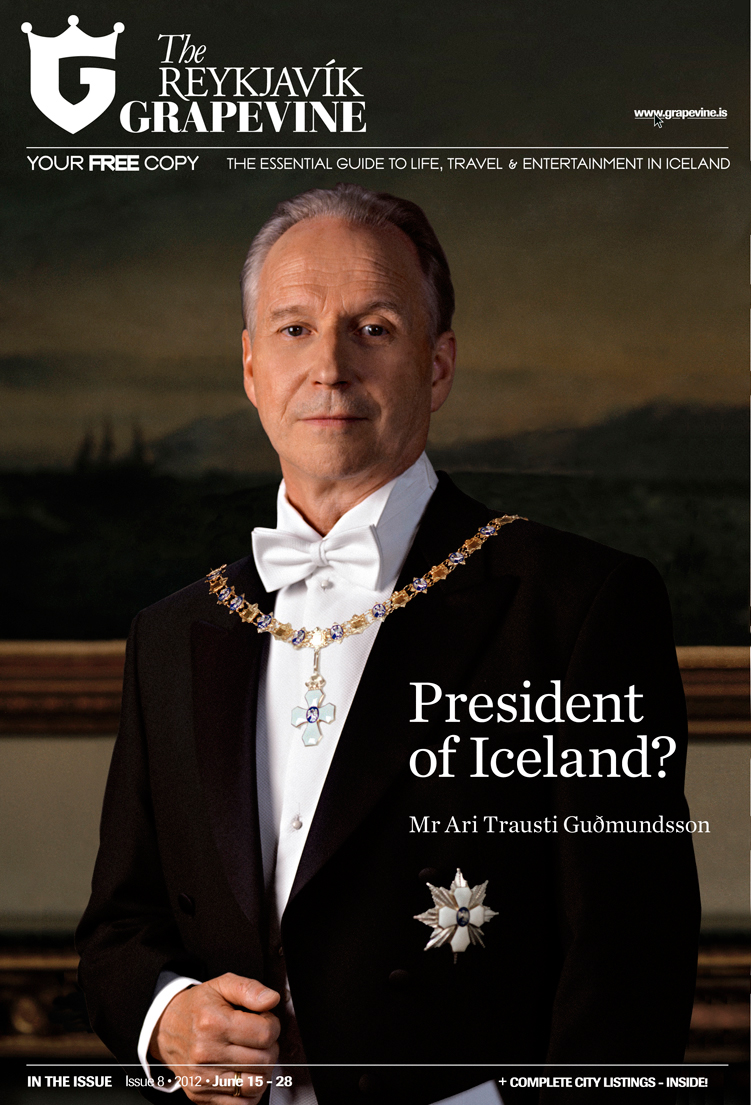

Ari Trausti Guðmundsson

Ari Trausti Guðmundsson

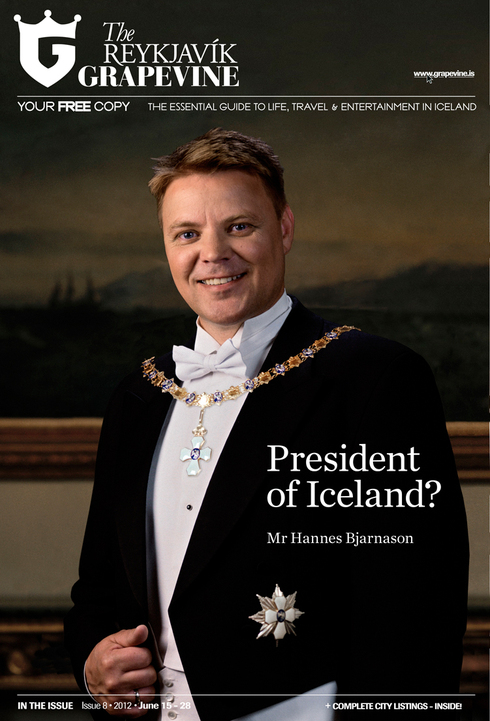

Hannes Bjarnason

Buy subscriptions, t-shirts and more from our shop right here!