It is the things that we think we understand that inevitably catch us unawares. We all know what loans are, and what mortgages mean, so we don’t bother questioning them as we sign on the dotted line to pay up for the next 25 years or so of our lives. That at least, is the best explanation I can come up with for the existence of the most unique instrument of financial self-destruction over the last 30 years: the Icelandic Index Linked Mortgage.

UNDERSTANDING MORTGAGE REPAYMENT SCHEDULES

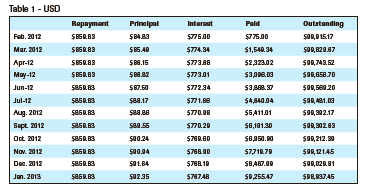

To appreciate the full financial havoc that the mortgages sold during the bubble years are slowly wreaking on the Icelandic economy requires an understanding of how loan repayments usually work, which means examining the loan amortization table for these loans. Loan amortization tables are something every borrower should get to know intimately. Quite simply they show the monthly loan payments, broken down into the amount of interest and principal repaid, and the amount of the loan still outstanding. If we use a $100,000, 25 year US loan at a 9.3% annual interest rate as an example, the first few months of its amortization table would look something like in table 1.

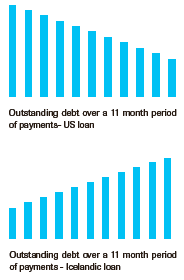

The table shows the monthly repayment broken down into the interest on the loan, and the principal repayment, and the total amount of the loan still outstanding every month in the ‘Outstanding’ column. Like all compound interest loans, at the beginning of the loan most of the money you pay goes on interest, with principal repayments being a depressingly small part of the total. At least though, in a typical US loan the principal outstanding on the loan is decreasing.

NEGATIVE AMORTIZATION LOANS

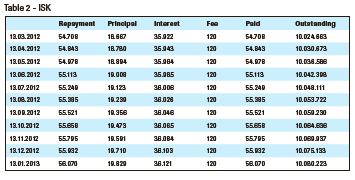

Compare and contrast the amortization table below for a notional 10 million ISK, 25 year Icelandic Index linked loan, taken from Arion Banki’s website, for the “Verðtryggð íbúðalán með föstum vöxtum” with an interest rate at 4.3% and an assumed constant inflation rate of 5%, together making the same total interest rate as the American loan shown in table 2.

There’s good news and bad news in this table. The ‘good’ news is that the repayments, initially at least are significantly less than those on the American loan. The bad news is what that will end up costing you, as the Icelandic Housing loans sold during the bubble years weren’t just index linked—they were structured as negative amortization loans.

Negative amortization loans are a specialized form of lending, supposedly only for ‘sophisticated’ investors, a term widely used within the financial industry to mean ‘gullible’. With NegAm loans, the initial repayments on the loan aren’t sufficient to cover the interest payments on the total amount borrowed, and so as you can see, the total amount of the loan increases over time, rather than decreasing. As the amount of interest you pay on the loan depends on the amount of the principal outstanding, then the next month the interest payable on the loan also increases. The lower payments last at most eight years (assuming nothing dramatic happens with the inflation rate), at which point according to the Arion Bank’s calculator the principal owed is still climbing. Indeed it isn’t until 17 years after the loan has been taken out, that the original loan begins to be repaid.

HOW BAD CAN IT BE?

In comparison to an American 25 year mortgage for $100,000 at 9.3%, a borrower would end up repaying a total of just over $257,000. With an Icelandic, NegAm Index 25 year linked loan for 10 million ISK, at 4.1%, and assuming a stable inflation rate of 5%, the borrower would end up paying slightly more than 31 million, or the notional equivalent of $310,000 if we drop a couple of zero’s.

While paying 5 million more ISK than a comparable loan in the US (or Europe) would cost might not seem so bad, in fact the majority of the loans sold during the bubble period in Iceland weren’t 25 year loans; they were 40 year. The Arion Banki calculator shows that the total repayment for a 40 year loan of 10 million works out to be 65 million ISK. A comparable 40 year US loan by comparison, would come to $380,000.

Recently it has become possible to get five year fixed rate loans at 6% in Iceland, and anybody who can is well advised to do so. Whilst these still don’t match what’s available in America, since the interest rate after the 5 year fixed period is adjustable, they’re still a far better option than the old NegAm index linked loans—which are still available, both from the banks, The Housing Financing Fund, and in doubtless well meant offers on local real estate listings to take over the existing loan and avoid having to put down a 20% deposit.

The real comparison, though, isn’t with a 9.3% US loan since most people don’t pay that kind of rate over there. Fixed rate 25 and 30 years loans can currently be had in America for around 4.5% to qualified borrowers. The total repayment on a 4.5% fixed rate 25 year loan, is just under $167,000, nearly $140,000 less than the 9.3% 25 year Icelandic loan. All of which assumes that nothing dramatic happens to the inflation rate, and for Iceland at least, 5% is decidedly on the low side as an inflation estimate.

Now while you might think, and indeed I have frequently heard it argued here, that the high inflation rate somehow justifies this form of robbery by math, this ignores the important question of what causes inflation in the first place. In particular, it ignores the cause of inflation in Iceland, which is usually the direct consequence of the badly regulated lending activities of its banks. Always accompanied by a nice story from the salesman about how house prices always go up and it would always be possible to sell for more than the loan.

In fact with negative amortization loans the direct opposite tends to be true, since it is difficult, if not impossible, for borrowers to build up capital while repaying them. Quite often borrowers simply end up selling the house for the total amount still outstanding if they are lucky. However there is no guarantee that the house price will increase as quickly as the outstanding loan amount will, so if they are unlucky they’re left in negative equity and have to sell for less than the loan and bring extra money to the table to close. As the steady flow of foreclosures in Iceland bears mute testimony to, many Icelanders can’t even do that.

Buy subscriptions, t-shirts and more from our shop right here!